When Boba Phil made us go all misty-eyed and gooey over The Last Starfighter a few days ago, it made me get all nostalgic about days gone by. About better times. Simpler times. It put me right in the mood for some more Hollywood History and reminded me of something we wrote about at our old site.

So back from the ashes, let us take a stroll once more through the world of pure imagination that is visual effects.

We take it for granted now. Photorealistic, computer-generated visual effects (VFX) that create worlds and action beyond our wildest dreams. In many ways, it has depressingly started to replace character and storytelling in many Hollywood movies.

Now that nothing is impossible on screen, do we even have to dream it anymore? That is a depressing thought. While considering the question “How did we get here?”, let’s look at the Hollywood History of special effects.

Ingenious Beginnings

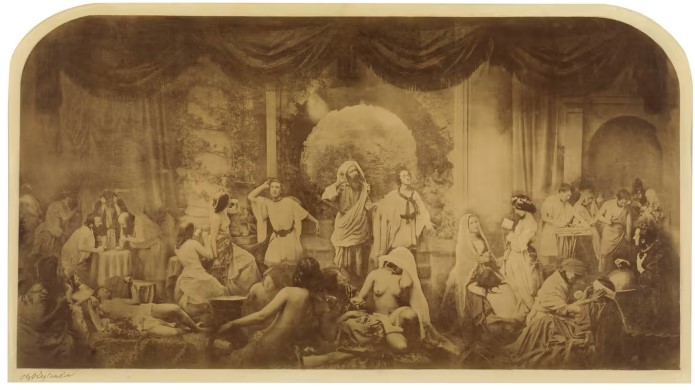

Oscar Rejlander is known as the Father Of Photography. In 1857 he created what is considered the world’s first special effect image by combining different sections of 32 negatives into a single image, making a montaged combination print. This famous photograph is called The Two Ways Of Life.

In 1895, Alfred Clark created what is commonly accepted as the first-ever motion picture special effects by adapting some of Rejlander’s techniques. He created a reenactment of the beheading of Mary, Queen of Scots for Edison Film.

He instructed an actor to step up to the block in Mary’s costume. Then as the executioner brought the axe above his head, Clark stopped the camera and had all of the actors on set freeze.

The person playing Mary stepped off the set to be replaced by a dummy. He then restarted the camera, allowing the executioner to bring the axe down, severing the dummy’s head.

Little did he know it at the time, but he had created a technique that would endure for almost a century.

Straight To The Moon

In 1902 Le Voyage Dans La Lune was the Avatar of its time and left viewers stunned.

They had never seen anything like the entire world depicted on screen. The effects were mostly all the work of George Melies, who directed hundreds of short films before working on the masterpiece. Melies brought together everything he knew about special effects to create this film, including double exposure, split screens, and dissolves and fades.

He also used some animation techniques in certain sequences. To understand the birth of animation around this time we need to consider The Enchanted Drawing.

In the film, the cartoonist for the New York Evening World, Stuart Blackton, draws a cartoon character and then adds things like a top hat, a bottle of wine, and an empty glass. He then pulls the other items out of the picture and the picture’s expression changes as they interact together.

Decades ahead of its time, the short was met with wonder. Watching it today you can see the foundations for many techniques we now take for granted.

The best known of these really early animations, though, was Gertie the Dinosaur, a short film that featured newspaper cartoonist Winsor McCay interacting with an animated brontosaurus.

This is the first known example of a person appearing to enter animation and interact with the cartoon. Sometimes it is mistaken as the first animation ever, but this is not the case. Even so, an actor entering an animation is a well-used trope, and a much-loved visual effect, even today.

Another technique to allow actors to interact with early visual effects is forced perspective. It is still used today, even in Bond movies such as The Living Daylights for the bridge destruction scene in Afghanistan, or The Lord Of The Rings whenever they wanted hobbits to interact with bigger creatures.

This effect technique dates all the way back to 1900. The British 22-second film by director R.W. Booth and producer Robert W. Paul called A Railway Collision is generally agreed to be the earliest example of this practice.

This technique developed further through model use and then perfected by placing two negatives together on top of one another to allow the model work, at the forced perspective, to seemingly interact with an actor.

The most famous early example of such model use was 1925’s The Lost World. This ground-breaking film featured actors interacting with giant monsters. Willis O’Brien, who was later involved with King Kong, used small puppets that were filmed one frame at a time on mini-sets. The actors were then added by using the negative overlay technique.

Paint It For Me

These days it seems easy to insert actors into digital worlds. But what about when computers didn’t exist? Instead, painted backgrounds were often used to portray most settings. Giant glass panels were originally placed behind the actors during filming. The first time this was done was in the 1907 film Missions of California, which used a massive matte painting of crumbling missions.

Possibly the most famous use of this technique was in The Wizard Of Oz where glass matte paintings allowed Dorothy to travel to a massive city made of emerald.

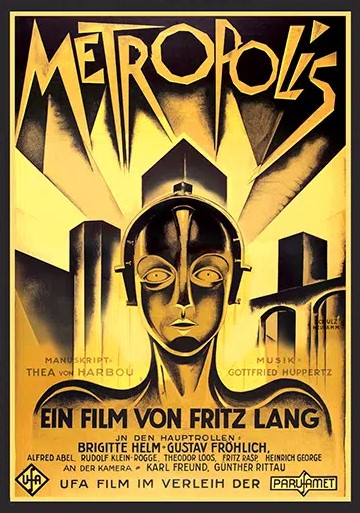

If the background needed to move, such as a dust cloud or weather effect, directors would often use a background projection instead. This required playing footage of the background on a screen behind the actors, then filming both at the same time, in the same frame. If the creatives had the ingenuity, and the patience, then they really could accomplish wonders, such as in the 1927 film Metropolis.

Director Fritz Lang managed to create elaborate sets by projecting the top of a massive-looking building – often just a model – onto a mirror located in the top portion of the camera frame.

The camera would then shoot the actors performing in front of a wall so that there was the appearance that the tops of the impressive sets, seen in the projection, were a continuation. As you can see in the trailer, they also used a lot of models to create these vast and impressive urban cityscapes.

A Blue And Green World

Even a local weather person uses this sort of technology now, but back in the day, it was possibly the biggest leap forward in VFX techniques. Today, the simple version is that you just tell a machine to put video “A” everywhere that blue appears in video “B” and there you have it, two images combined in motion. However, what if there were no machines?

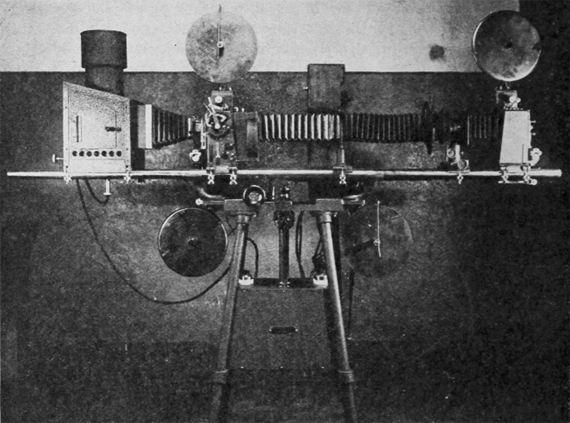

When The Lost World portrayed humans running away from stop-motion animated monsters, they actually had to shoot film on an early optical printer. They would then have to manually block out all but the actors on the top film, then blocking out where the actors would appear on the stop-motion film. Finally, they could combine them onto a third roll of film.

Expensive, time-consuming, and ultimately not sustainable. However, it took until 1940s and a new version of The Thief Of Bagdad to crack the riddle and start using a blue screen behind the actors. This enabled the makers to print only the actors on one roll of film.

Using this method, the film would be developed with a number of color filters to ensure that the blue background would disappear. As if by magic, only the actors and intended background would show up. The world of VFX, and movies in general, was once again revolutionized.

Nowadays, a green background is more commonly used. Why this great technological leap from blue screens? It is simple. Back then, nobody could wear blue on-set or they would disappear on the film. Blue was chosen because it is the furthest color in the visual spectrum from red, which is the main color in human skin tones.

Today’s cameras, in particular video cameras, have digital sensors highly sensitive to the color green so that color now trumps blue as being far away from flesh tones and easy to block out.

Rise Of The Machines

One of the great debates in movie geekdom is digital vs. practical. Many claim that CGI technology still looks inferior to well-done animatronics. These tricky and complex effects actually were first used over 100 years ago, when Richard Murphy created a mechanical eagle for D.W. Griffith’s first appearance in Rescued From An Eagle’s Nest in 1908.

Of course, animatronics have always been a natural home for the portrayal of cinematic monsters. This bird started it all and set the stage for everything from the giant quid in 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea to Jaws or a T-Rex in Jurassic Park.

There are far, far too many to detail in writing, but here are a few favorites.

From animatronics, it is not a huge leap to the advent of computers and Computer Generated Imagery (CGI). Today an ubiquitous tool used across the filmmaking spectrum, even CGI had quite humble beginnings in the industry.

The history of CGI goes back to the 1950s. Early mechanical computers were repurposed to create patterns onto animation cells which were then incorporated into a feature film. A very early example of CGI is Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958).

John Whitney used a WWII anti-aircraft targeting computer on a rotating platform with a pendulum hanging above it. This created the spiral elements in the opening sequence which Whitney worked with Saul Bass to insert into the title sequence. And so computer animation was inadvertently born.

It was still very crude. Another big step forward came when John Whitney Jr and Gary Demos digitally processed motion-picture photography, this had the result of creating the pixellated POV of Yul Brynner’s gunslinger robot in Westworld.

A blend of models, matte painting, camera movement, and rotoscoping was used to create one of the most famous sequences in motion picture history. Staggeringly, no early CGI was used in that movie – 2001: A Space Odyssey.

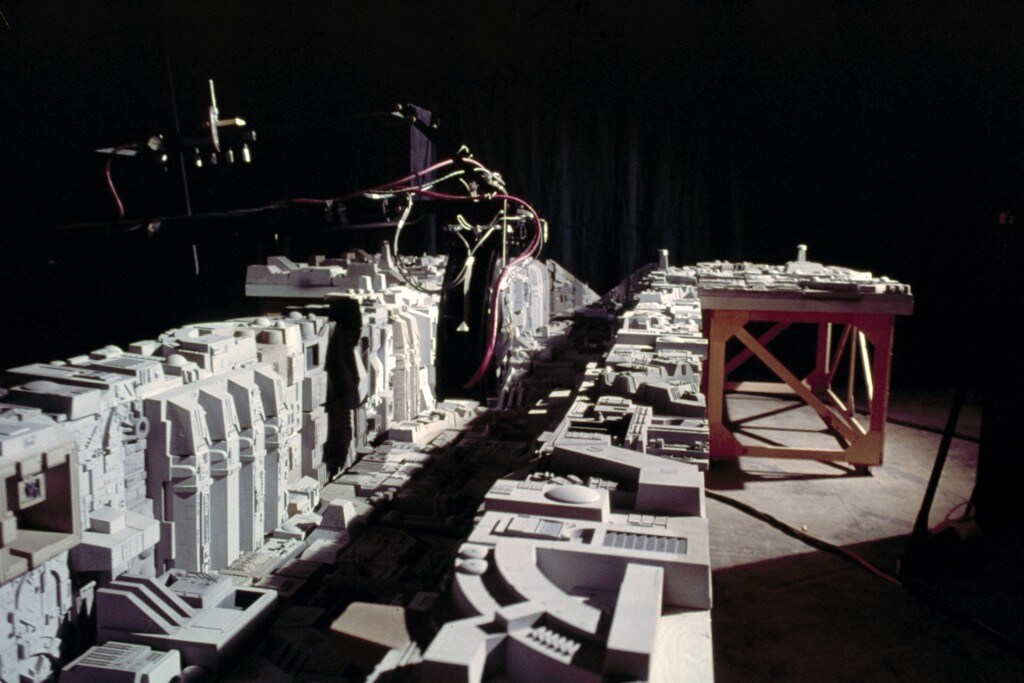

The sequence did provide inspiration to a certain George Lucas, who harnessed computers to control the speed and the movement of cameras working with detailed miniatures to allow a galaxy far, far away to come to life. Lucas also went one step further by incorporating an actual computer animation in his movie, Star Wars.

In the trench run briefing sequence, George Lucas brought digital to Hollywood. It was the first step in a journey he would pioneer throughout his career.

Larry Cuba, who worked out of the Electronic Visualization Laboratory (EVL) at the University of Illinois, explains his part in the computer graphics sequence for Star Wars in the video below.

These computer animations, computer-controlled effects, and computer-generated images were still largely separate from the actors. This would change with 1982 and Disney’s Tron. The original idea for Tron was intended to be a combination of animation and CGI, but with the high cost of animation at the time it was decided that a combination of CGI and live-action would be cheaper. That cost-conscious decision delivered a movie that used computer animation, live-action, and backlighting to change the world of VFX forever.

From here a line was drawn that can be traced through The Last Starfighter to Jurassic Park, the Star Wars prequels, right up to Avatar. The world of movies changed forever, but it happened over a longer, more gradual process than we may realize.

So where next? Will virtual reality ever really take off? Will there be yet another 3D resurgence? Or is there a yet unseen new FX opportunity lurking around the corner?

Check back every day for movie news and reviews at the Last Movie Outpost