The spooky month of October is upon us. Soon we will weirdly decide to celebrate the supernatural at Halloween by dressing our children up up as ghouls, vampires, or a werewolf.

Then we will send them out to demand candy from strangers, in their own home, under menace of trickery.

We also see this as a chance to think about some of our favorite horror movies.

This is a double celebration, as not only do we get to think about some firm Outpost favorite movies, but we have also unmasked a lurker! An Outposter known as Sammers has walked among you for some time, and he has chosen to reveal himself in the most spectacular way possible, with a contribution.

We love a contribution here at Last Movie Outpost. Nothing makes us happier than an Outposter stepping forward. And what a way to make an entrance! Look at it!

Do you want to take your place as a legend among Outposters? Got something you want to share? Send it to us at [email protected].

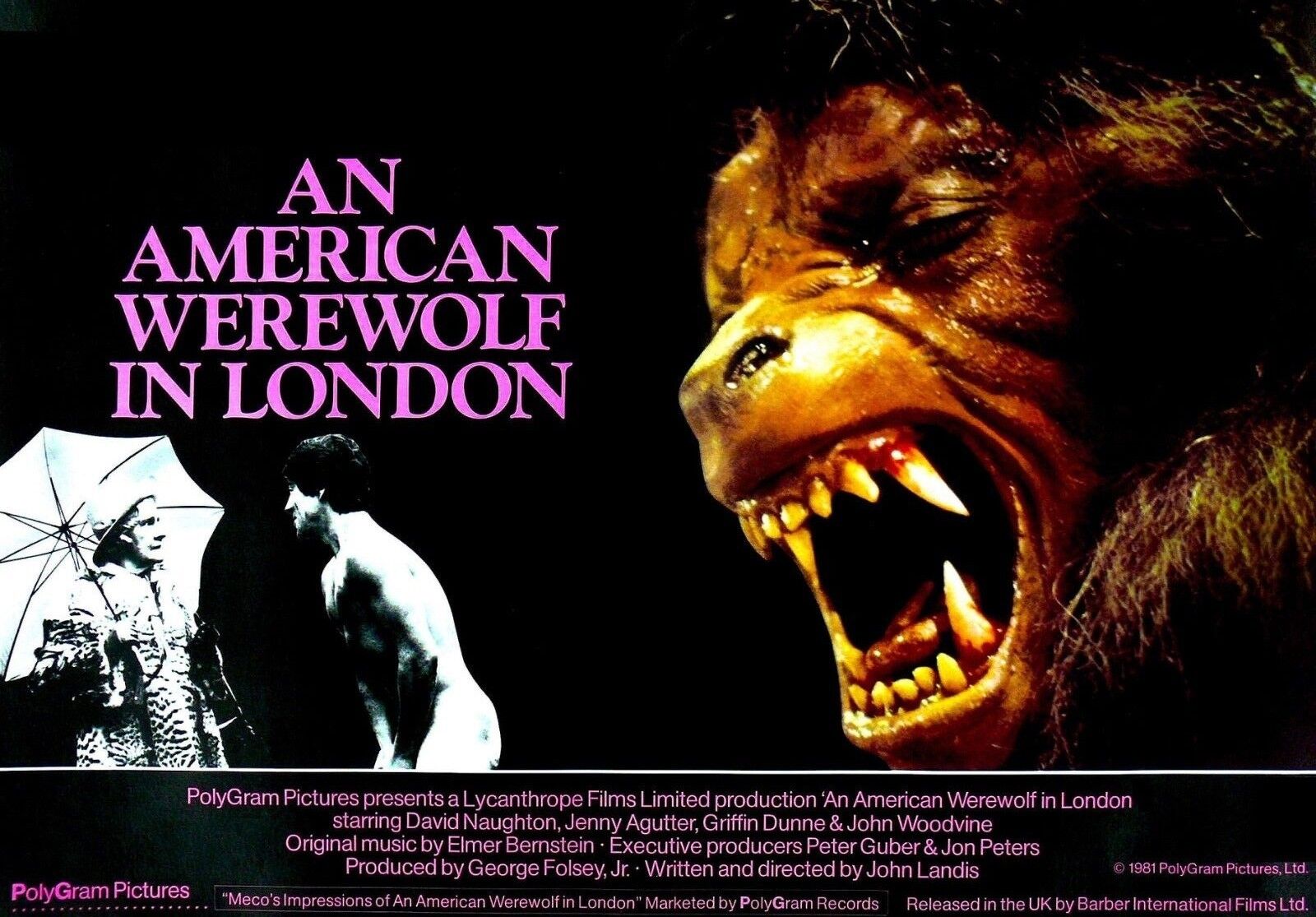

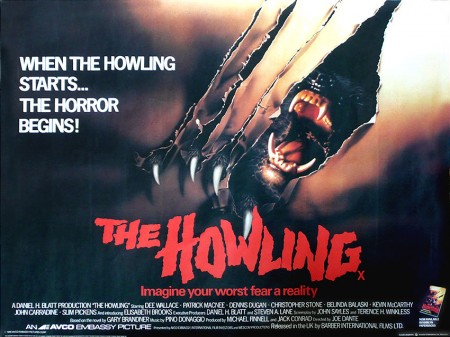

Here is Sammers and his Halloween head-to-head between arguably the two greatest werewolf movies of all time – An American Werewolf In London and The Howling.

The Howling Vs. An American Werewolf In London

Werewolf movies were always my favorites of the horror genre. God knows why. There are so many terrible ones. “Best of” lists are usually the same familiar titles with only the order changing.

Dog Soldiers. Ginger Snaps. The (original) Wolf Man. Wolfen (which I’ve never much liked). The Company of Wolves (which I kind of do). The Wolf of Snow Hollow had an interesting take on the genre. Late Phases… almost, except the werewolf looked absurd.

The top two spots will always be reserved for The Howling and An American Werewolf in London, both of which released only months apart back in 1981.

While both films are still lauded to this day, there’s always been this Marvel vs DC rivalry between them, where folks tend to favor one camp over the other.

They are, without question, my two favorite werewolf movies, but I jump back and forth on which one I prefer.

Some days, I just can’t decide.

This Halloween, it occurred to me that I’ve always wanted to take a closer look at both films side-by-side, weighing up all their different aspects.

So, that’s what this will be. Part review, part comparison, part retrospective, and part analysis.

I’ll be comparing the scripts, direction, transformation scenes, and each werewolf design, and maybe we’ll finally see which movie comes out on top.

The Beginning

Landis got the idea for An American Werewolf in London in 1969, while working as a production assistant on Kelly’s Heroes (1970) in what was then Yugoslavia.

One evening, Landis and another crew member were being driven home when they stumbled on a Romani funeral. The procession had gathered at a crossroads and was in the process of burying a corpse wrapped in muslin cloth and bound with garlands of garlic.

When asked why this was happening, the Romani replied that the man had been killed while committing a serious crime. They had to bury him in this fashion or else he might return and cause trouble for them later.

Landis found this bizarre, and it got him wondering: how would rational, educated people really cope when faced with something ancient and supernatural?

The plot this would eventually form into is one of those perfect little ideas that could fit on the back of a postage stamp.

American college students David and Jack are backpacking across Europe. One night, lost on the English moors, the boys are attacked by a werewolf.

While Jack is killed, David survives only to find himself cursed to become a werewolf at the next full moon.

There’s an awkward romance in there too, but that’s really about it. It’s very barebones.

The Howling was written by John Sayles, based loosely on the novel of the same name by author Gary Brandner.

It doesn’t have a cool, real-life origin story like American Werewolf, but it does have more going on in terms of its plot:

When a rendezvous with serial killer Eddie Quist nearly costs Karen her life, she finds herself plagued by nightmares and amnesia. On the advice of a therapist, she travels to “The Colony” – a therapeutic retreat out in the countryside.

Once there, connections between Quist (who might not be so dead) and the Colony’s strange residents are soon revealed.

Both are pretty standard werewolf fare, but like all good horror films, each script offer up a healthy dose of subtext, too.

The Script

In The Howling, the Colony works well as a satire of the self-help craze of the 1980s. There might even be a venereal metaphor festering under its skin, with key scenes involving sex shops, peep shows, and shady doctor’s offices.

This is a movie where people transform not screaming in pain but amid shuddering orgasms.

American Werewolf is far less sardonic, but more interested in the psychology of its characters.

Jack and David’s friendship works so well that you accept David’s trauma following the attack. Landis cleverly constructs all of David’s nightmares from the same sudden violence he fled from on the moors, and soon enough it all starts to feel like a meditation on survivor’s guilt.

Jack constantly urges his friend to take his own life, but as Jack’s a walking meatloaf, his advice feels suspicious, like there’s an unpaid debt left between them.

The Howling doesn’t really have that level of complexity, though (to be fair), it’s not really attempting it either.

Maybe because of the novel, Sayles’ script feels the fuller, more robust story of the two. He has more characters with broader personalities to juggle, but his script never loses focus, winding up its separate beats in a mostly satisfying way.

The third act, where Eddie’s connection to the Colony is revealed, is a bit convenient, but the script always keeps its tongue firmly in cheek, so you forgive it.

The big climax involving werewolves barbequed inside a barn, as well as Karen’s final news broadcast, are both great fun, and work nicely within the movie’s cheeky tone.

Now, maybe because it sticks its neck out a little bit more, problems with Landis’s script are more obvious on repeated viewings.

David and Alex’s romance never feels fleshed out. The way he comes to live with her, not to mention most of their dialogue, is porno level in terms of believability.

1980s smoke show, Jenny Agutter, receives the worst of it with lines like:

“I’m torn between feeling very sorry for you, and finding you terribly attractive.”

To be fair, Agutter is great in the film, and her final scene in that alleyway provides genuine empathy to a climax more concerned with carnage.

Overall, American Werewolf has a script that feels like a much leaner beast, never spoon-feeding you like The Howling does. There’s no occult bookstore, no Dick Miller, no convenient tome on werewolf lore.

In fact, there’s very little exposition at all. It’s refreshing, and even leaves you feeling slightly vulnerable, but some of those omissions do feel closer to plot holes.

We learn zilch of what connection existed between the original werewolf and the townsfolk of East Proctor (if any).

They all seem terrified of the werewolf, but then wind up dispatching it fairly easily. If they knew it could be harmed by regular weapons, what was the hold up?

This is more thoughtfully addressed in the effective BBC radio adaptation from 1997, where the chess-loving pub patron, now named George Hackett (and again played by Brian Glover), is given a meatier role.

The first werewolf is now a troubled member of their parish, and George Hackett’s own brother (hence everyone’s reluctance to deal with it).

It’s a clever repackaging of Landis’material and gives their motivations a bit more shape.

In Landis’ script, even though The Slaughtered Lamb has some of the film’s more famous lines, it never feels totally fleshed out as an idea.

Their reasoning for kicking Jack and David out so quickly also feels underdone. All Jack asked was what the candles were for. It’s a good question; I’m wondering the same thing.

Is the pentangle altar keeping the werewolf at bay, or is it more of a shrine, and they secretly worship the creature? We’re never shown.

Had Jack accidentally knocked the altar over or damaged it or something, then I could buy their sudden banishment. But these points are minor. Where Landis’s script suffers most is in its bizarre third act.

The tension of the first half of the movie builds splendidly until we hit a crescendo with the first transformation sequence.

After a night of mayhem, David arrives back to Alex’s flat early, and though she attempts to take him to see Dr Hirsch, they never make it; David soon learns of the previous night’s murders and flees, overcome with shock.

Now, I’ve watched American Werewolf probably a hundred times over the years, and my best guess is that, after running off, David finds Jack, and then enters the porno theatre at some time around midday.

Inside, we get the classic suicide pep-talk scene. Then the next thing you know, Big Ben’s striking eleven, and David’s about to transform again.

Was he seriously sitting in that theatre all day? You’d think at the very least he’d try and go someplace less populated. Maybe where there aren’t innocent perverts sitting around?

To me, this time jump always felt jarring.

You’re expecting the story to circle back to East Proctor in some way, back where the curse began. I could buy David convincing himself (out of desperation) that the locals know of some way to break the curse. It would’ve connected with the script’s survivor’s guilt theme, too.

Again, the BBC radio drama attempts to fix this by extending Brian Glover’s role.

In this version, George Hackett sets off to London with the intention of finding David and killing him, thus ending the curse that originated with his brother.

It’s a cool little twist that allows those earlier scenes to feel more organically involved, while also reintroducing Hackett in the third act as a kind of antagonist for David.

Unfortunately, for the movie’s sake, Landis seems more interested in getting to that final rampage in Piccadilly Circus.

Even though David’s now convinced Jack was right all along, he does nothing to remove himself from a heavily populated area, and simply stays put, waiting for the worst to happen (again).

We still get a fun finale with the wolf tearing through Piccadilly Circus, but it feels bombastic alongside the film’s more mature, intimate tone.

I’ve barely mentioned The Howling in this section, and that’s a good thing. That script has a far more satisfying third act, and there’s far less to nitpick overall.

Comparing the two, it’s hard not to appreciate The Howling’s more cohesive structure, which I’ll chalk up to John Sayles being a more skilled screenwriter.

For script, I’ll score it 1-0 to The Howling

Direction

While there are similarities, each director attacks the subject matter in different styles.

The Howling looks like a lurid Hammer film, filled with hard shadows and gothic fog, but it has its own grindhouse vibe, too.

Once at the Colony, moonlight shining through fog looks almost neon; not too far removed from the scuzzy lighting of those opening scenes in LA.

It’s a neat visual cue that Karen hasn’t quite escaped her nightmares yet.

It’s impressive the ease at which Dante constantly flips tone between genuine creepiness and camp.

This is a movie where cans of Wolf Chilli hide like Easter eggs in every frame, where Robert Picardo digs a bullet out of his skull, and Roger Corman lurks around phone booths, pilfering loose change.

Likewise, the film’s violence is savage, but never overly gory. You can tell Dante’s relishing in throwing his hat into the ring, but the name of the game here is fun. He keeps the overall atmosphere unsettling, but mostly in a dreamlike way.

A good example of all this is when Terry gets hers in the doctor’s office.

She’s digging up dirt on Eddie Quist, but like in a dream, as she reaches for the incriminating evidence, the movie turns on her, and it’s the werewolf’s gnarled fingers reaching in to frame to pluck the folder from her grasp.

It’s a fantastically off-putting moment; the drawn blinds, the dark, deserted office filled with charts, stacks of paper, common place things.

When the drama turns, everything familiar now flips, twisted by that same liminal dread that Dante will use again to great effect in Gremlins (1984), a few years later.

On the other hand, American Werewolf is a bit unusual in that it expects to be taken somewhat seriously, even while everyone in the movie is constantly pointing out how absurd it is.

It’s funny, too, but its humor’s never at the expense of its central concept. It’s cheeky, but never fourth-wall breaking, like the cans of Wolf Chilli in The Howling.

The cinematography by Robert Paynter looks a bit like an old painting, with deep reds, dusky blues and hard-edged shadows. At times, it resembles a kitchen sink drama more than an 80s horror film, and there’s very little manipulation in terms of where the camera’s placed.

We’re simply shown what’s there, and if we can’t see something, then neither can the characters.

The violence is directed very matter-of-factly, with Jack’s death remaining one of the more memorable murders in any horror movie of that era.

His desperate pleas while being mauled is still deeply unsettling, and Dunne’s performance is so good it makes you forget he’s only wrestling with a puppet.

Another moment permanently burned into my brain is that hysterical ticket woman, screaming for help outside the porno theatre. The way she stands there, shrieking, while the police try and understand exactly what’s happening, feels real.

With a few exceptions, these actors aren’t mugging for the camera. If you want to see the difference, watch 1997’s An American Werewolf in Paris — then destroy your copy with fire.

Elmore Bernstein’s score (a standout) is minimal, used only at key moments, but rather than trying to overcompensate, going for jump scares, his use of piano feels sad, and the overall mood, combined with the lingering camera work, especially early on, is closer to mournful.

Because of this, the direction feels slightly dated — but in the best possible way. Sort of how The Exorcist (1973) feels“boring” compared to most modern horror films.

The scene where David calls his sister from a pay phone, says goodbye, then puts a knife to his wrist, is directed very precisely, using only a few intimate close-ups.

The moment plays honestly, never straying into sentimentality, and weirdly is probably the most mature scene Landis has directed

It’s close, but I’m giving the directing points to American Werewolf, if only because it takes the more difficult road in trying to make this feel realistic, and it mostly succeeds.

Score: 1-1

Metamorphosis

A complaint often levelled at American Werewolf is that the movie is just a special effects reel to hang a story on.

While it’s probably true that nothing else in the movie quite reaches the spectacle of that scene, what Landis and Baker achieved here is so much greater than stretchy prosthetic hands and change-o-heads.

The sequence works on a story level first, something you often don’t see in werewolf films.

As an adult, one thing I’m struck with is how profoundly tragic it feels. If American Werewolf is really a meditation on David’s guilt and grief, then this is the moment when those emotions finally spill over from his mind to wreck his body.

Naughton’s performance really carries this scene. It’s hard to believe that the guy was only known for a Dr Pepper commercial at the time.

The way his eyes frantically dart around the room, searching for anything that might offer comfort, is as terrifying as it is sad.

One moment that always hits me is that cutaway to Mickey Mouse.

I know its purpose is so that they could switch practical effects mounts (one change-o-head for another), but in the context of the scene, it’s somehow terribly sad.

What should be a symbol of childhood instead taunts him: not only are you far from home, you’re far from the man you once were, and now you’ll never be that person again.

Alongside Naughton’s performance, Baker’s practical effects are incredible and still stand up to this day.

Of all the influences American Werewolf is known for today, the most overlooked is that transformations are painful affairs, filled with ruptures and dislocations.

It seems an obvious choice now, but prior to this, werewolf transformations typically had the actor sit perfectly still so that the various makeup stages could be applied one lapse-dissolve at a time.

Baker had originally urged for David’s transformation to occur in one shot, with each body appliance stretching and morphing shape at the same time.

Landis cautioned that this would not be as dramatic as showing each body part morphing separately, in close-up.

The transformation was shot last, after principal photography wrapped, so Baker’s team had extra time to work out any kinks.

Simple tricks were used, like having the actor stand inside a hole cut into the set, so that only the wolf’s body was visible below his head.

Footage of hair begin pulled through prosthetic skin was reversed giving the impression of it sprouting.

As The Howling uses many of these techniques, it’s worth mentioning that both films share some behind the scenes history too.

Joe Dante had originally hired Rick Baker to handle the special effects work on The Howling.

Baker had a verbal agreement with Landis, but at the time it didn’t look like American Werewolf would get made, so he took The Howling gig and didn’t tell Landis about it.

As it turned out, Landis would get the green light while Baker was still in pre-production.

Out of loyalty to Landis, Baker would then exit Dante’s film, passing the gig over to his protégé, a young Rob Bottin, who’d go on to have a legendary career himself.

Because of this, Eddie Quist’s transformation shares similarities with David’s, but it doesn’t quite carry the same story weight, and Dante’s execution is very different.

Rather than the fluorescent lighting of Alex’s flat, Doctor Waggner’s office is gloomy, filled with shadows. Aesthetically this adds to the atmosphere, but it also serves to hide limitations in the prosthetic devices worn by actor Robert Picardo.

These werewolves aren’t cursed like David Kessler, at least not as far as we’re told. They can change shape at will, and Eddie’s transformation plays out like something he enjoys.

His breathing deepens, his chest puffs out, he grins as his face distorts and claws sprout from his fingers. But he barely moves—probably because the effects weren’t designed with that in mind—and this only makes the scene feel longer than it really is.

Like Landis, Dante cuts back and forth from one appliance to the next; some of which look great, like the gangly, clawed fingers, or the way expanding limbs rip shirt fabric.

But close-ups of Eddie’s face in certain shots look less convincing. It just doesn’t have the articulation or detail of Baker’s work, and the moody lighting doesn’t quite save it.

I think the other issue (and it’s common in the werewolf genre) is that except for revulsion we don’t feel anything for Eddie, and this in turn shifts emphasis on to the effects rather than Picardo’s performance.

There’s no humanizing moment like the Mickey Mouse shot in American Werewolf, and I think this hurts this scene the most. It’s just not as character driven.

After repeated viewings, you feel the movie grind to a halt just to watch Bottin’s work come to life, and as impressive as it is, it ultimately feels more like a showreel than a piece of storytelling.

We cut back to Terry several times, but her terror can’t hide the fact that she’s only standing around, waiting.

She does very slowly reach out for a conveniently placed jar of acid, but then somehow waits until he’s fully transformed before flinging it at him.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s still a dynamic scene, but alongside American Werewolf, it feels a bit shallow by comparison, and slightly long in the tooth.

For transformation, American Werewolf gets the point: 2-1

Creatures

Landis made an interesting choice in making his monster a big, demonic wolf rather than the two-legged variety. You don’t often see that done, but while conceptually interesting, I don’t think the decision did Baker and his team any favors.

The final wolf was achieved several ways, depending on the shot needed.

For wides, a performer laid down inside the suit while a puppeteer lifted their legs, walking them along like a wheelbarrow. That’s why you never see the wolf’s rear—the performer’s feet would’ve been sticking out.

While a novel way of getting around the whole quadruped problem, it’s not flawless.

We don’t get a really good look at it until Piccadilly Circus, and by then so much tension has been built that the effect really has a lot riding on it.

David’s rampage isn’t played for yucks, and the moment he bursts through the roller doors of the theatre it’s treated as if a dangerous animal were loose in the street.

That wolf better look real, or else it won’t match with the film’s realistic tone.

But the creature never moves very convincingly, especially in wide shots. There’s one shot in particular where the werewolf trots down the street, and its back legs barely touch the ground.

Had they favored quicker cuts, or shooting from behind objects, or in reflections, it might’ve held up better. It’s not terrible, it’s just portrayed a little too shamelessly.

In the years since, Landis has admitted he probably did show the thing too much but was so in awe of Baker’s work at the time, he couldn’t help it.

There’s an excellent shot of it in the tube station, shot from a high angle, above the escalator, but this works best because we only get a glimpse as the creature enters frame.

For close ups, it’s a big hand-puppet; and it’s these quicker shots, where the only detail you absorb are its amber eyes and snapping jaws that work the best.

I’ve always felt its overall design was too barrel-chested and low to the ground. The head lacks articulation and looks small on that massively wide body.

Baker said he intentionally sculpted its face into something that would stick in your memory, even if you only glimpsed it. But Landis shows the damn thing so much I can’t help but notice how comically large its teeth are.

It’s still a very cool creation, certainly memorable, but it doesn’t hold a candle to what Rob Bottin cooked up for The Howling.

We get our best look when Terry’s attacked in Waggner’s office.

As the werewolf backs her against a wall, shoving furniture aside, swiping with its claws, you get a real sense that this thing’s not only huge, but impossibly strong and fast.

The werewolf was only built from the waist up (its legs were puppeteered separately, and shot in cutaways), but the way Dante blocks the scene, having it knock things over, cutting away to separate shots of its feet padding around, help sell the illusion of a living creature.

It doesn’t look more “real” than Baker’s werewolf, but it does somehow look (and move) far more believably.

When it lurches forward, swiping with its claws, there’s a physicality to the way it’s puppeteered, and Dante’s use of simple, effective editing, really sells it.

He shoots around the werewolf, building its presence, rather than showing the thing marching down the street.

It’s a lesson Landis should’ve heeded, and a key difference in the way these films were executed visually.

Speaking of, when designing their monster, Dante encouraged Bottin to ignore the more humanoid variants films like as The Wolf Man (1941) and Curse of the Werewolf (1961) had favored, wanting a more animalistic look.

Bottin’s final design is tall and mangy, almost diseased looking, with sharp lupine features, and was influenced mostly by how werewolves were depicted in old woodcut engravings from the middle-ages.

You can really see the influence with Bottin’s werewolves feeling more like monsters from a fairy tale brought to life.

There are a few iffy moments — namely when rotoscoping and even stop animation is used to achieve the creatures standing in wide shots — but it’s used sparingly and never detracts from the work’s overall quality.

Overall, these werewolves are effective, memorable, and still very threatening. In fact, I’ll go so far as to say The Howling has the best werewolves yet put to film.

Final Score: 2-2

Conclusions

So, there it is. After all that we have a draw.

Going in, I felt The Howling might come out on top, if only because I’ve come to appreciate it more over the years, whilst noticing some of American Werewolf’s failings.

But it’s hard to judge these two films against each other. While they’re similar enough to compare, their differences tend to stand on their own merits.

For what it’s worth, I still think American Werewolf is the more flawed of the two, mostly due to its plot holes and third act. But Landis’ direction lifts that film, even when The Howling’s is more consistent and enjoyable overall.

In the end, they’re both all-time classic werewolf movies, yet-to-be topped. This genre was perfected back in 1981, and nothing can ever change that.

Hollywood is apparently attempting remakes/reboots of both films, and while I don’t hold much hope, I’ll prepare some silver bullets just in case.