Once more, we find ourselves gazing lovingly back at what was our very own Golden Age of cinema – the 1980s. A time of flickering myths, reasonably priced tickets, and heavy petting in the back row. This is why we often had to watch movies again, at home. So strap in, dust off your Betamax, and prepare to squint lovingly at Krull, a movie that absolutely believed it was about to change cinema forever… until it didn’t.

Krull

There is a very specific subgenre of early-80s cinema that only exists because Star Wars made a gazillion-billion dollars and every studio executive on Earth briefly lost their mind. This insanity also met the rise of Dungeons and Dragons as a pastime, and movies like Conan The Barbarian also making a splash. So, this new subgenre stumbled awkwardly into the light.

Anything with swords, spaceships, glowing objects, or vaguely medieval haircuts was immediately greenlit with the hope that they could make lightning strike twice, and Krull is perhaps one of the purest distillations of that madness.

On paper, Krull was meant to be Star Wars meets Lord of the Rings. In reality, what we got was something closer to Flash Gordon meets Hawk the Slayer, filtered through a haze of dry ice, shoulder-length hair, and the sincere belief that throwing enough concepts at the screen would somehow coalesce into a classic.

And yet. And yet…

Despite being kind of a mess, Krull is still fun, inventive, and undeniably charming in that very specific “they tried really hard and failed loudly” way that only the greatest decade of the 1980s could produce.

This is not a great movie. But it is a very Krull movie.

Battle Beyond The Budget

Krull takes place on the planet Krull, because of course. It’s one of those fantasy worlds where medieval castles coexist with laser-shooting alien invaders, and consistency is for cowards.

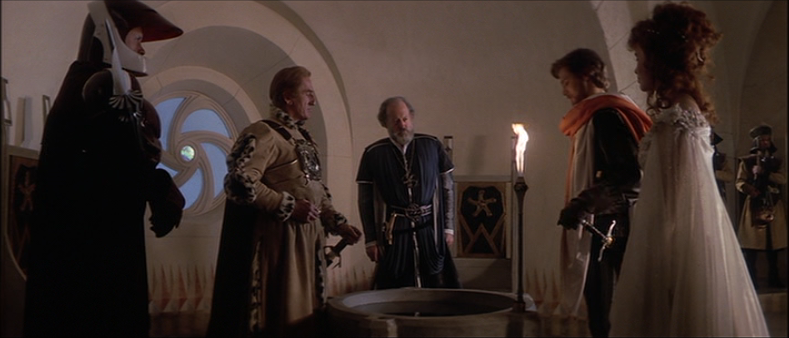

The story kicks off with Prince Colwyn (Ken Marshall, jawline first, personality second) marrying Princess Lyssa (Lysette Anthony, wandered in from a perfume commercial). Their wedding is rudely interrupted by the minions of The Beast, a demonic alien warlord who lives in a shape-shifting mountain fortress and commands an army of faceless, black-helmeted goons.

The Beast’s minions kidnap Lyssa, because the plot demands it, murder Colwyn’s dad for the same reasons, and so send Colwyn on a quest to retrieve her. Along the way, Colwyn must assemble the obligatory ragtag band of warriors, thieves, cyclopes (cyclopses?), and elderly wizards who may or may not be senile.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because it’s every fantasy and sci-fi trope thrown into a blender and then poured directly into a leather jerkin. Of course, any story like this needs a mythological weapon. No mere sword of destiny would do for Krull. So enter the Glaive. Awesome, iconic, and also completely useless.

A five-bladed, gold, throwing star-come-boomerang is hidden inside a lava pit because it just is. It’s introduced with such reverence that it feels like Excalibur, Mjolnir, and Luke’s lightsaber all rolled into one. Which is probably why it is such a crushing disappointment within the movie.

Visually? It is fantastic. One of the coolest weapons ever designed.

Practically? The most useless weapon in the history of cinema.

To use the Glaive, Colwyn has to stand perfectly still, throw it very carefully, hold out his hand and wait while it slowly flies back, hope nobody stabs him while he’s doing all this, and then try not to lose his fingers, or even an entire lower arm, when trying to catch it. It’s less a weapon and more a trust exercise.

However, in the lore of Krull, it can kill anything, even The Beast, but only if the movie is almost over and the plot says it’s allowed to work. In every other situation, it behaves like a majestic frisbee that occasionally remembers it has murderous intentions.

Rampaging around this silliness alongside Colwyn is a cast seemingly designed to fuel a “spot the future British star” drinking game. It features Liam Neeson, pre-Taken, pre-Jedi, pre-everything, looking about twelve and swinging a sword. Robbie Coltrane, years before Hagrid, doing his best not to steal every scene. Patrick Malahide, because of course Patrick Malahide is in this, and Alun Armstrong, adding gravitas like it’s his job… because it is.

Here, at the very beginning of their careers, there’s something oddly endearing about watching actors who would later command serious respect running around in fur vests and headbands.

Ken Marshall, as Colwyn, does his best, but let’s be honest: he’s mostly there to look heroic, swing swords, and react earnestly to things exploding behind him. Lysette Anthony, meanwhile, floats around as if she’s sponsored by a shampoo named Destiny.

An Eye On Tragedy

Just when all this silliness gets really… er… silly, then a bloody Cyclops appears and anchors everything to some feelings that, as a kid, you had only felt when your Dad told you the dog had gone to live on a farm.

Every fantasy movie has an obligatory character that has to serve as the emotional core, but in Krull, that honor goes to Rell the Cyclops. He is a cursed warrior who knows exactly when and how he will die. This is way heavier than it has any right to be.

While everyone else is bantering, stealing horses, or failing to use the Glaive correctly, the Cyclops is quietly carrying around existential dread like a champ. His storyline is genuinely moving, and when his fate finally arrives, it lands with surprising weight.

For a movie that features teleporting castles, flying fire horses, and disco-helmeted soldiers, Krull suddenly pauses to remind you about mortality.

Then it immediately goes back to sword fights. Perfect.

These heroes face off against The Beast. This villain is a classic case of less is more, mostly because the less we see of him, the better he works. He’s part demon, part alien, part “we ran out of budget for a full reveal.” His fortress, however, is legitimately cool. A giant black mountain that teleports around the planet like it’s late for a meeting.

The production design meeting about the inside of the fortress must have been hilarious. When given a choice of inspirations, either a heavy metal album cover, a haunted house designed by HR Giger, or a laser tag arena for Satan himself, somebody high up decided with all the enthusiasm of a Terminator in a gun store – “All”

The corridors move. The walls kill people. Everything is sharp, angular, and actively hostile. It’s one of those great 80s practical sets where you can feel the crew sweating under hot lights while dry ice floods the floor.

The Beast’s army consists of anonymous, chrome-masked soldiers who are essentially the Krull version of Stormtroopers in that they look cool, they march menacingly, and they miss constantly. Their main function is to get stabbed, thrown off cliffs, or dramatically blasted by weapons that should not logically exist in a medieval setting.

They are there to remind you that despite the movie’s fantasy trappings, Star Wars is absolutely living rent-free in this script.

Ambition Meets Reality

Krull was directed by Peter Yates, a genuinely talented filmmaker who had previously made Bullitt. This was not a hack job. This was a serious attempt at building a new fantasy franchise.

The production was enormous for its time. Elaborate sets. Extensive location shooting. A full symphonic score by James Horner, who was clearly giving it 110% because he hadn’t yet learned to phone it in. There were behind-the-scenes clips everywhere. Magazine articles. This was to be an event. A “thing”.

The problem? Well, for a start, there is the tone.

Krull never quite decides what it wants to be. It’s too grim to be a kids’ adventure, too earnest to be camp, and too strange to be mainstream sci-fi. It lives in that awkward middle ground where everyone involved is taking it very seriously, while the audience is quietly wondering why medieval peasants are fighting space aliens.

When it was released in 1983 it underperformed at the box office. It wasn’t an outright disaster, but it didn’t come close to justifying its budget. Then there were the critics. They accused it of being derivative, overlong, confused, and impressively expensive for something so silly. Which is, to be fair, accurate, but also kind of the damn point.

Like many films of its era, Krull found a second life on cable TV, VHS, and late-night broadcasts, where expectations were lower and imagination did more of the work.

But here’s the thing. Krull may be clumsy. It may be overstuffed. It may have a featured weapon that requires a user manual and a prayer. But it’s also full of ideas.

There’s creativity everywhere. Practical effects. Miniatures. Matte paintings. A willingness to mash genres together and see what happens. Modern blockbusters could learn a thing or two from that kind of fearless weirdness.

Krull isn’t ironic. It isn’t cynical. It genuinely believes in itself, and that goes a long way.

Krull might not be the epic fantasy it wanted to be, and definitely was not the franchise starter Fox hoped for, but it is a glorious artifact of a time when Hollywood threw money at imagination and hoped the audience would follow.

It’s messy, it’s strange, it’s frequently ridiculous, but it’s still kind of awesome, and we all want a friend like Rell and a Glaive of our own to throw around.