Back in the mists of time, before the previous iteration of our wonderful Outpost went spectacularly wrong due to a massive SQL database issue that made Drunken Yoda cry, we were writing about a lot of Hollywood History. Well, to paraphrase Luke Skywalker, nothing is ever really gone. Thanks to the wonders of technology, we can revisit some favorites that were previously thought lost.

This time, we look at the history of one of cinema’s greatest art forms. A technical skill that brings our imaginations to life. The history of movie miniatures and model making.

The Magic Of The Miniature World

It is a simple fact that without the skill and dedication of an army of miniature creators and model makers throughout cinema history, many movies we know and love today just simply would not exist. They make the impossible, possible.

A filmmaker will often talk of the search for truth, but what if that truth is too dangerous to create, such as an explosion bigger than a building? Or prohibitively expensive, such as a cityscape. What if the ask is impossible, like an alien world or a giant spaceship? Well, then that is when movie magic comes into play.

If the movie calls for a physical representation of an object that maintains an accurate relationship between most of its important aspects, that is a scale model. Also known as miniature effects, or simply miniatures. Their use is almost as old as film itself.

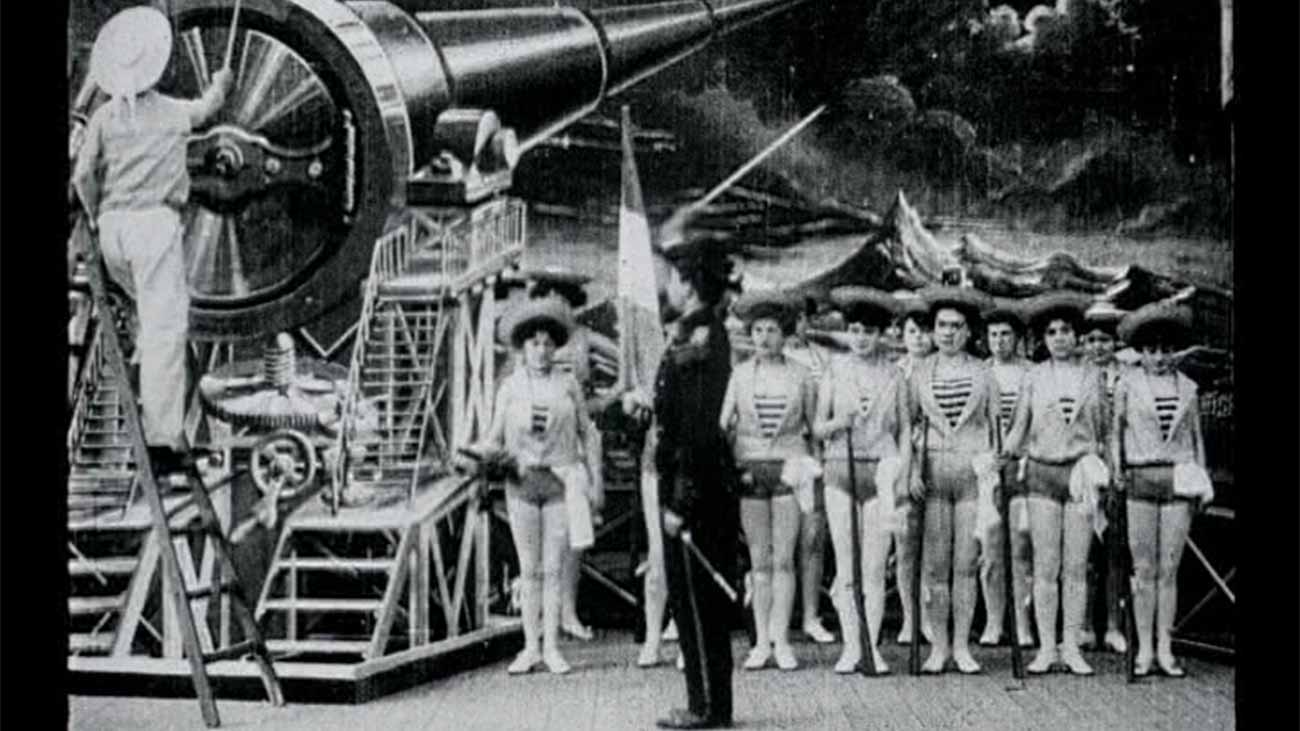

As we know from our previous Hollywood History articles, you can’t go anywhere near the history of the technical aspects of filmmaking without coming across French Filmmaker Marie-Georges-Jean Melies. The scholars of celluloid among you will know Georges Melies as the Father of Cinematic Special Effects.

It is no surprise to discover that Melies was one of the earliest users of miniatures. Le Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon) in 1902 made use of miniatures alongside the first recorded use of a number of special effects techniques such as split screens, double exposure, and stop motion.

The lunar surface and, of course, the spaceship were created as miniature models and they were placed on the set.

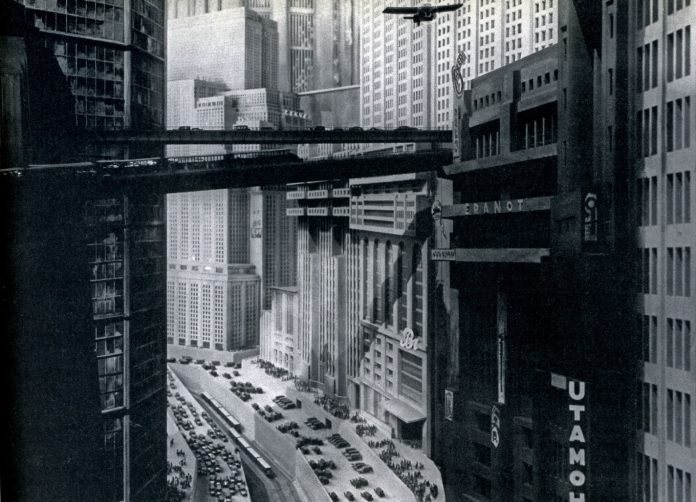

In just fifteen years, by 1927, cinema was ready for the next great leap forward as Fritz Lang’s game-changer Metropolis also made widespread use of models.

The German film created a futuristic, vast dystopian cityscape in miniatures then used the German Schufftan process with mirrors creating the illusion that actors are actually within the sets.

Around this time, the world of movies was changing rapidly. In Southern California, filmmakers were flocking to a dusty desert town in search of cheap space and natural light with clear skies.

Big Monkey!

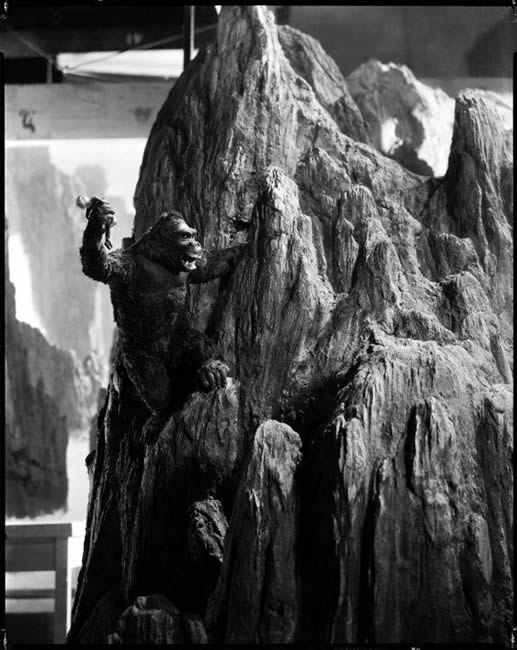

As movies grew in scope and scale, so did the demand for miniatures, until one day in 1930 a famous memo was written to help artist Willis O’Brien create an oil painting as previsualization:

“His hands and feet have the size and strength of steam shovels; his girth is that of a steam boiler. This is a monster with the strength of a hundred men. But more terrifying is the head—a nightmare head with bloodshot eyes and jagged teeth set under a thick mat of hair, a face half-beast half-human…”

And so King Kong was born. One of the earliest monster movies also had an incredible requirement for miniatures. Jungles, cityscapes, creatures – all were needed.

Directors Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack specified a scene where King Kong fights with the snake-like dinosaur. This would go on to be one of the most famous special effect moments in cinema history.

The scene used stop-motion animation among matte paintings, real water, smoke, foreground rocks with bubbling mud, a miniature set, and two miniature rear screen projections of Driscoll and Ann.

In this, models of Kong had to interact. These were jointed 18-inch aluminum, foam rubber, latex models covered in rabbit fur. Football bladders were used to simulate breathing.

Outside of the monsters, the Venture, railway cars, and the warplanes were all miniature models, as was the city Kong rampages through.

When making Citizen Kane in 1941, director by Orson Welles and crew planned every shot, set design, and camera movement with miniature models.

These were then expanded by the art director up to full-sized sets. These models also included lighting design. The walls of sets were designed, based on what was learned from the models, to fold and furniture was able to be moved easily. Ceilings were made out of muslin fabric and camera boxes were built into floors to allow low-angle shots to be captured without disruption. All made possible with meticulous miniature work beforehand.

Across the other side of the world, a director called Ishiro Honda was working on another creature feature that would eventually go on to hold the record as the most extensive use of miniatures at that time in motion picture history. The 1954 Japanese film Godzilla.

A suit was created using thick bamboo sticks and wire, over which metal mesh, cushioning and latex coats were added until the finished Godzilla weighed over 100 kilograms. That was nothing compared to the work required to make something for Godzilla to smash.

40 workers from the carpentry department were required to work for over a month to build the city of Ginza. The Diet building was specially scaled to look smaller than Godzilla, and a number of buildings were built with pre-installed explosives inside ready to become victims of Godzilla’s atomic breath.

While they were bringing to life giant lizards over in Asia, the Americans were playing God… literally.

The Ten Commandments was released in 1956 and used a combination of giant sets and detailed miniatures to bring Egypt to life – some re-used from the 1954 movie The Egyptian. The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, and inflation-adjusted is the seventh most successful film of all time.

Seas were created in a u-shaped trough in miniature, then the direction of the film was reversed to create the illusion of the parting of the sea. All of the multiple elements of the shot were then combined in Paul Lerpae’s optical printer, including plate effects to insert Israelites and pursuing Egyptian soldiers, and matte paintings of rocks by Jan Domela to conceal the matte lines between the real elements and the special effects elements.

To Infinity And Beyond

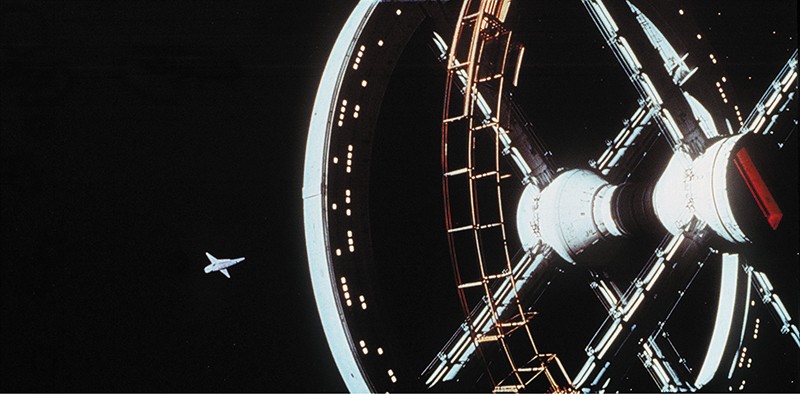

In 1968 the world of movie miniatures was changed forever by a return to outer space. Going full circle from where it all started, A Trip to the Moon, a movie with huge scale revolutionized the use of models and miniatures, including how they were filmed. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey would go on to be regarded as one of the most influential movies of all time.

The three-year-long production was a creative spark that allowed filmmakers to create convincing models of spacecraft and new camera techniques to bring them to life.

Some of these models were fifty-five feet long. These models were filmed directly by moving the camera instead of the model to create a sense of movement. Simple, yet effective.

Miniatures would continue to make incredible spectacle through disaster epics from filmmakers like Irwin Allen. The Poseidon Adventure (1972), Earthquake (1974), and The Towering Inferno (1975) are all notable for their exceptional model work. However, it is the sci-fi genre, sparked by Kubrick and then kicked into the public consciousness by a young George Lucas, where the real action was in the world of miniatures.

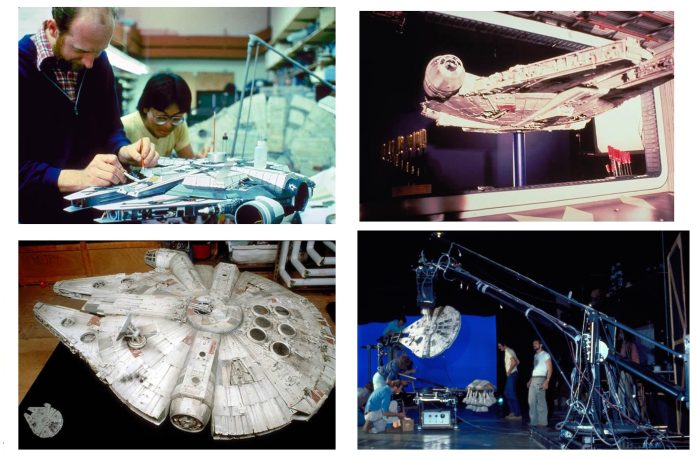

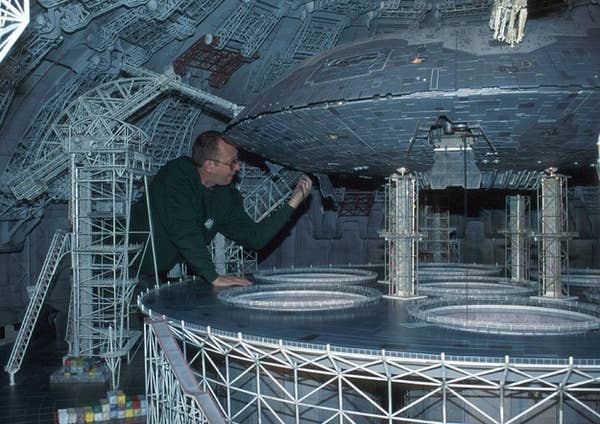

Star Wars (1977), Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977), Alien (1979), Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), and Blade Runner (1982) were all pushing the envelope further and further each time.

The design of the mothership for Close Encounters was inspired by an oil refinery Spielberg once saw in India. The model makers realized very early on that the lights were the most important part for creating the sense of otherworldliness. For dark shots, the structure was irrelevant, but the shape and the lights were important. This is why one of the UFOs is just an oxygen mask with lights attached to it.

For Star Wars, Lucas demanded they create his vision of a “Used Future” where things looked lived in. The models were no exceptions, with burn marks and impact points all over them along with other signs of wear and tear.

A lot of these movies were made in what was becoming the center of the world for skilled craftsmen in the world of movies – the United Kingdom. In studios like Pinewood, Elstree, and Shepperton, American productions bought the money to make use of the facilities and the skills.

Attracted by advantageous tax breaks, these productions gave the craftsman the opportunity to expand their skills further, bringing to life legendary visions from giants of the special FX world like Douglas Trumble and Denis Muran.

Long before this rapid expansion of American sci-fi to the East, a young model maker was already making a name for himself.

The Model Maker’s Model Maker

Working straight from art college at Denham Studios, lettering credit titles, a young Derek Meddings met effects designer Les Bowie who asked him to join his matte painting department. While there he also dabbled in model making and create Transylvanian landscapes for Hammer Films.

This skill set brought him to the attention of Gerry Anderson. After working his way through the special effects ranks, including on Stingray (1964) he was unleashed fully on Thunderbirds (1965–66) and was responsible for designing and building the iconic vehicles as well as locations like Tracy Island.

He stayed on working with Anderson through other series like Captain Scarlett and UFO. Meddings and his teams developed a number of innovations in the filming of miniature models and landscapes which have since become standard in the industry. It was these innovations, along with his skill and imagination, that led to FX supervisors like Denis Muran and Douglas Trumble stating that they considered Meddings the best of all time when it came to scale models and miniatures.

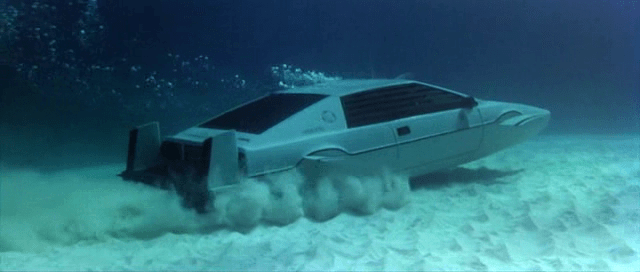

Meddings would go on to form a lifelong association with the Bond franchise, where his ingenuity made notoriously economically minded Cubby Broccoli understand the huge potential for building detailed miniatures rather than expensive, full-sized creations.

After Live and Let Die (1973) and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974) Pink Floyd sought him out. Meddings handled all the pyrotechnics on the Pink Floyd shows on their 1975 tour.

He spent four months on location in the Bahamas, building a 60ft (18m) long supertanker model as well as three model nuclear submarines. He also designed and built “Wet Nellie”, the Lotus Esprit submarine. In the movie, it is practically impossible to tell when the full-sized body shells and one-quarter-scale miniature submarine cars change places.

In 1979, NASA’s Space Shuttle program had not yet carried out a launch so Meddings and his miniatures team had to create shuttle launches without any reference footage for Moonraker (1979). Bottle rockets and signal flares were used for take-off, with his legendary ingenuity coming into play again by creating smoke trails with salt that was allowed to fall from the models.

The climactic scenes of the space station disintegrating were created by Meddings and other members of the special effects team shooting the miniature model with shotguns.

Meddings was nominated for an Oscar for his efforts on Moonraker against the backdrop of a tight budget and incredible time pressures.

Meddings would work with the Bond franchise through to GoldenEye, when he passed away shortly before the release of the movie.

Outside of Bond, one of his most famous projects was Superman (1978). Here he built a 60ft (18m) miniature of the Golden Gate Bridge that was able to be destroyed by an earthquake, complete with a colliding scale school bus and cars.

He also built and photographed the Krypton miniatures in addition to a large-scale model of the Hoover Dam.

Due to Superman schedule overruns, Meddings had to leave the production and return to James Bond with the damn flooding sequence still to be shot. A California-based company was hired and you can actually see the difference between Meddings miniature scenes and those in the flooding sequence. The drop-off in quality is jarring.

Meddings also worked on Batman (1989) because director Tim Burton was a fan of his work on Thunderbirds. He created the new Gotham City from the ground up with production designer Anton Furst. Meddings also appeared once as an actor, in the role of Dr. Stinson in Spies Like Us.

The Changing Of The Guard

Miniatures created some truly memorable scenes in more modern cinema, including at the hands of James Cameron for scenes like the tanker truck explosion from The Terminator (1984) and the bridge destruction in True Lies (1994).

Computer-generated special FX started gaining prominence from the early 1990s and miniatures slowly gave way to digitally created sets. When Jurassic Park landed, it was a complete game-changer. However, miniatures, their loving creation, and careful use refuse to be banished to the mists of time.

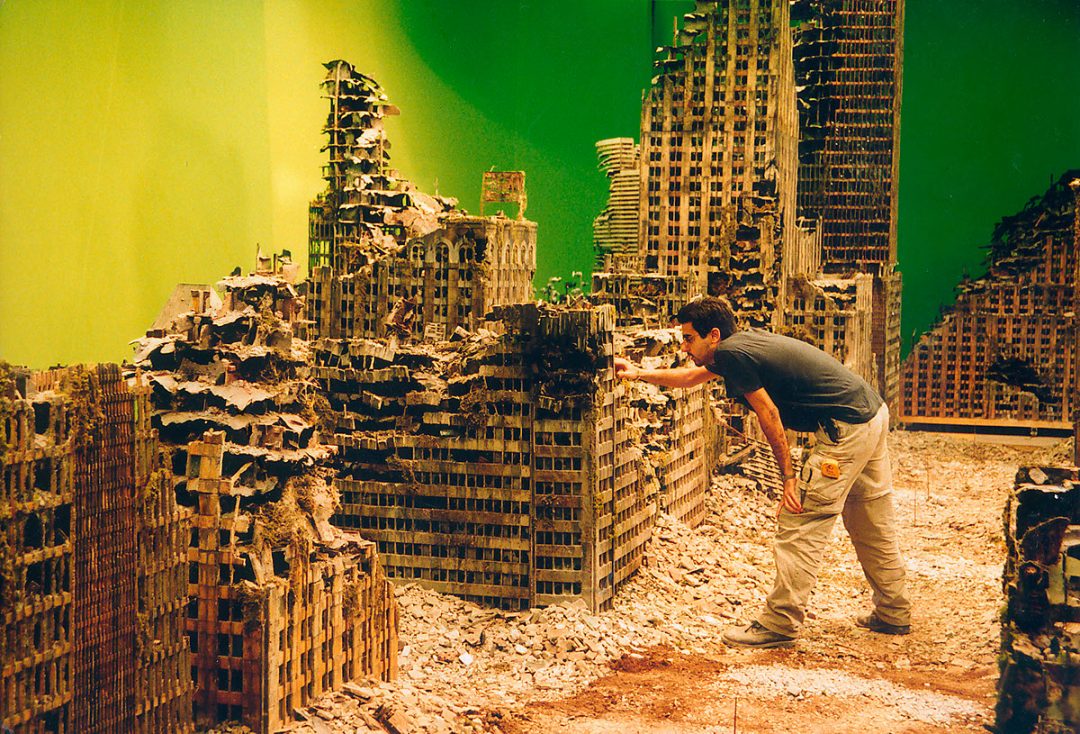

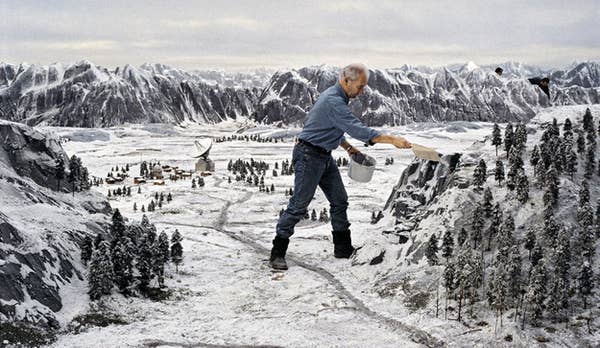

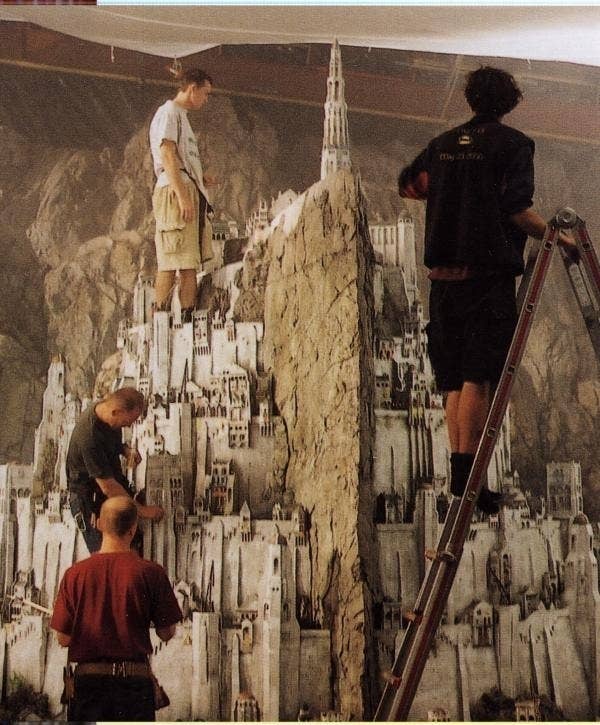

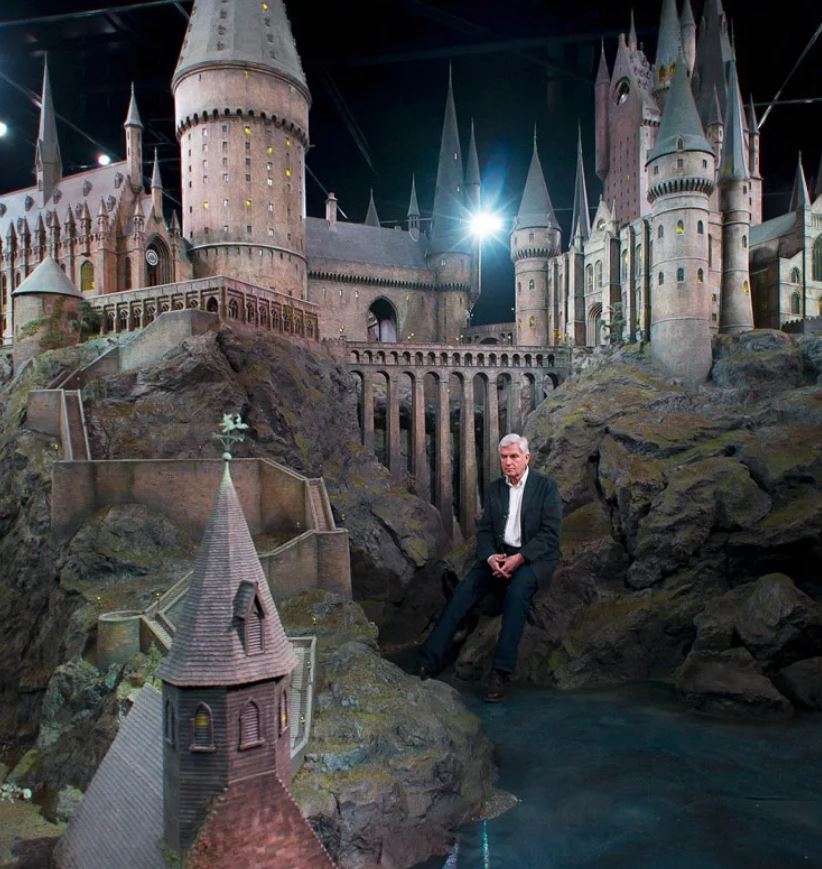

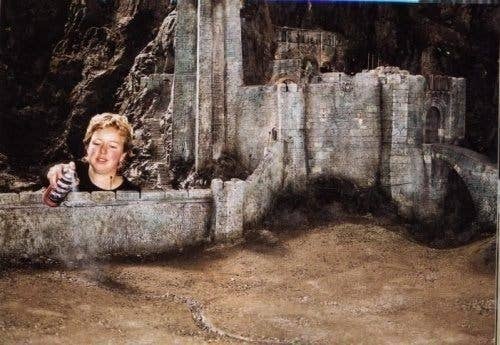

Lord Of The Rings locations like Minas Tirith, Rivendell, and Barad-dur are miniatures, as is the snow fortress in Inception and Hogwarts in Harry Potter. Even elements of Metropolis in Superman Returns were created by modelmakers.

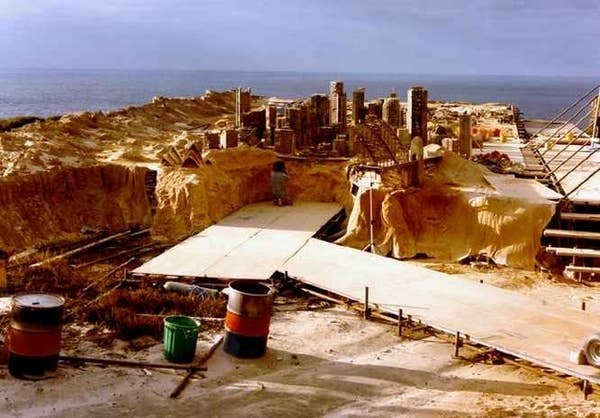

Here are some of our favorite movie miniatures, old and new.

Suddenly I have a strange urge to get up in the attic and build myself a model railway.

Check back every day for movie news and reviews at the Last Movie Outpost