Jaws started something, and we are not just talking about a lifelong fear of swimming in the sea. It started a wave of glorious knock-offs. From Piranha to Grizzly, if it could bite or claw, it was game for a movie. As the 1970s turned into the 1980s, this wave began to subside, but not before one last hurrah. Alligator (1980) is arguably the last of the great Jaws-inspired rip-offs.

There are movies that gently suggest danger. There are movies that escalate suspense. Then there are movies that throw everything in your face while screaming at you that, if Jaws kept you out of the sea, this is going to make you fear the sewers, the lake, your toilet, and even your own backyard swimming pool.

It is a movie about consequences, and those consequences are hungry.

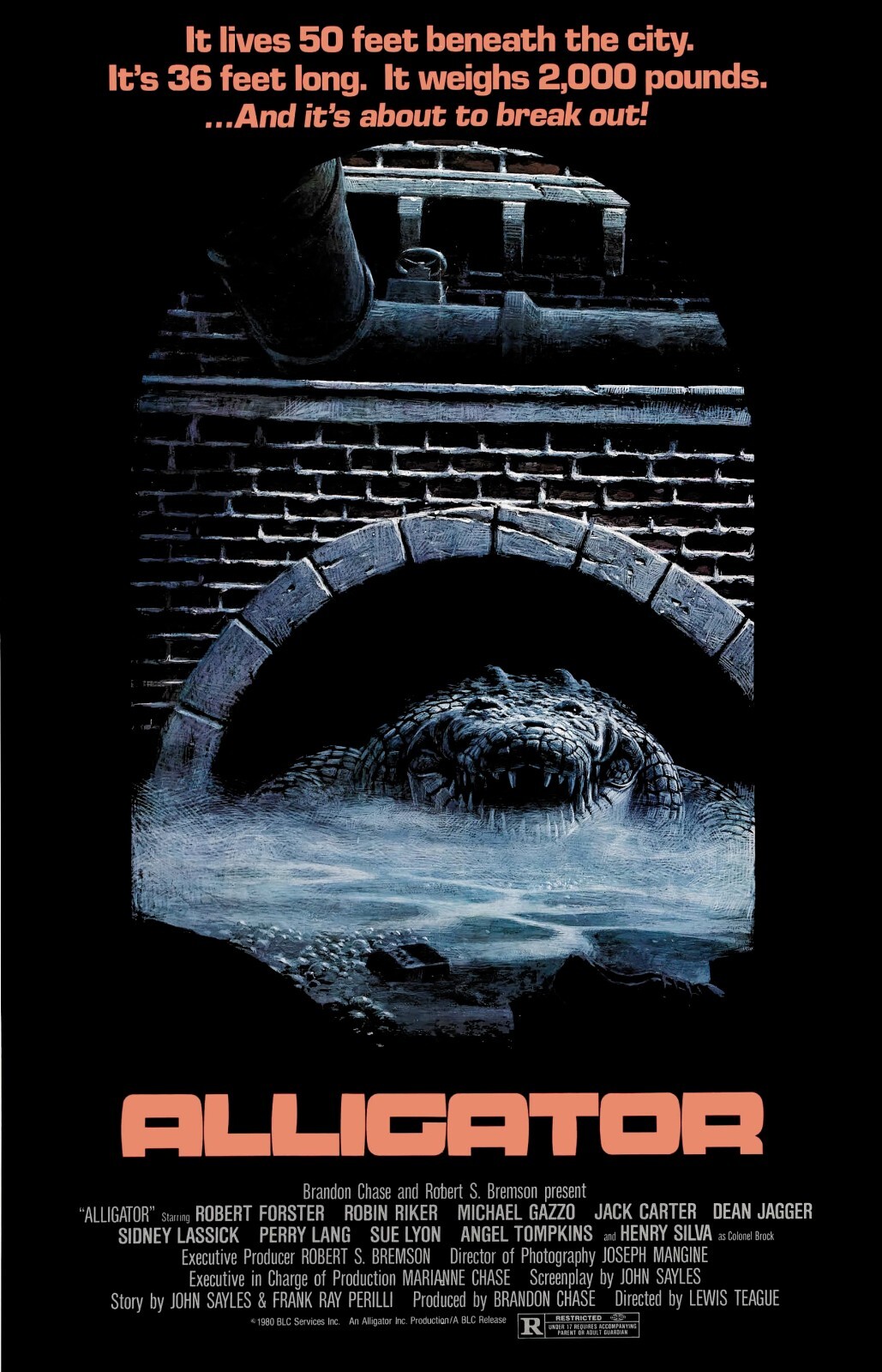

Alligator

This is not prestige cinema. This is blue-collar monster mayhem, forged in the dying embers of that knock-off gold rush. There was still just about life in rubber monsters, exploding blood squibs, and civic incompetence as long as they were blended perfectly.

Speaking of blood, Bryan Cranston worked as a special-effects assistant on this film, in charge of making and rigging “the alligator guts” for the film’s finale. Anyway…

Alligator exists because someone, somewhere, asked what if the scariest place in America was not a beach or a forest. What if it were around your own city?

It starts right off the bat with weaponized childhood trauma. A little girl, and a cute baby alligator named Ramone, as a vacation souvenir that would never, under any circumstances, exist north of Florida. When Ramone outgrows his welcome (and his tank), Dad demonstrates the kind of parenting decision-making that would get you banned from every group chat these days, and flushes him.

Just like that. Goodbye, Ramone. Down the pipe… and into legend.

This single act creates a cinematic butterfly effect that results in dozens of people dying horribly, municipal budgets exploding, and a wedding turning into a reptile-themed apocalypse. Pay attention, folks. This is what happens when you don’t rehome your pets responsibly.

John Sayles really does bring his arthouse soul to bear for a grindhouse paycheck here. The script feels like someone lost a bet. This is a man who would go on to make deeply human, socially conscious films, right after he lovingly constructed a screenplay where a sewer gator eats rich people for sport.

But Sayles gets it. He understands that the best monster movies aren’t about the monster. They’re about systems failing upward. So all required building blocks are present here. The city ignores warning signs. The police bungle everything. Corporations dump toxic science garbage where they shouldn’t. One of the proposed solutions treats urban infrastructure like a personal safari. Most importantly, the alligator isn’t the villain – it’s the audit!

The first major attack in Alligator does not ease you into things. There is no slow burn. There is no “maybe it was just an animal.”

Nope.

This movie kicks the door in. Investigating body parts that have already started to turn up in filtration systems, a detective and a volunteer junior rank go investigating, and it culminates in one of them being pulled, screaming, off an access ladder into the sewer below and violently torn apart, with enough blood and thrashing to establish that this is not a family-friendly creature feature immediately. This is an R-rated urban legend with a mean streak.

When Ramone finally shows himself, it’s sudden, brutal, and messy. The movie doesn’t cut away politely. It lingers just long enough for your brain to register everything. This isn’t a shark circling ominously. This is a reptile that has had years to build resentment.

You Yell Alligator…

From here on out, Alligator becomes a masterclass in institutional incompetence.

The police don’t believe it.

Then they half-believe it.

Then they believe it, but don’t coordinate.

Then they coordinate badly.

Traps are laid. Plans are made. Meetings are held. Nothing works.

At one point, a SWAT team is sent into the sewers, because apparently the city’s risk assessment boils down to: “Well, they’ve got guns.” When this succeeds in doing nothing but flushing the monster out into the general population, the results are spectacular.

Later, there is a speedboat-borne pursuit, and sheer incompetence leads to one poor SWAT guy gets his legs bitten clean off. Not wounded. Not grazed. Gone. It’s shocking, abrupt, and darkly funny in that way only late-’70s cinema could pull off without irony. The movie doesn’t pause for a moment of silence. It just keeps going.

At the center of the chaos is Robert Forster, delivering one of the most grounded performances ever put opposite a rubber monster.

Forster plays Detective David Madison like a man who has long ago accepted that reality is optional, and paperwork is eternal. He doesn’t quip. He doesn’t mug. He reacts to every new development with the exhausted resignation of someone who knows this will absolutely become his problem.

When everyone else is either panicking or posturing, Forster is quietly competent. He believes his own eyes. He connects the dots. He does the work. Which, in a movie like this, makes him feel like a goddamn superhero. The real miracle isn’t that he fights a giant alligator. It’s that he survives municipal meetings.

Cinema’s Most Traumatic Birthday

One scene in particular permanently rewired several childhoods. This is a kids’ pirate-themed birthday party in the evening. Balloons. Cake. Parents half-paying attention. The exact environment where adults assume nothing bad could ever happen.

The birthday boy is made to walk the plank, as a pirate, by his little pirate buddies. The plank is the diving board of the family poolm shrouded in darkness. Too late, the mother in the kitchen flicks the switch to turn the pool lights on, and…

Those screams were real, and they were yours. This scene did more damage to American pool culture than any PSA ever could. Entire generations learned that water is a liar, drains are portals, and birthday cake offers no protection.

Into this incompetence and horror steps Colonel Brock. He’s in this movie because every movie like this demands somebody like him. He’s Quint and Hooper rolled into one, but with a monstrous ego and a wandering eye. Arrogant to the point of comedy. When civic leadership inevitably fails, the city brings him in as the nuclear option.

Henry Silva is at maximum volume. Brock does not believe in subtlety. He believes in firepower, bravado, and treating urban spaces like they’re hostile territory in a 1950s war movie.

Brock conducts himself like he’s on a big game hunt, even treating the city’s residents of color as if they are his porters, to the point where he is seemingly moments away from asking them to carry his luggage on their heads.

Swaggering around in colonial cosplay, Silva plays him like a man who has never been wrong in his life. For all his bluster, all his macho posturing, the universal rules of movies dictate that a character like this must die, and so he does. Brock goes out in a moment of beautifully timed absurdity. No noble sacrifice. No heroic last stand. Just pure, cosmic slapstick justice.

It is hilarious. It is perfect. It is the movie laughing directly at him.

The movie gods also demand a wholesale slaughter scene, and this takes place at a society wedding thrown by the very people whose corporate negligence helped create the monster in the first place. It is, therefore, without exaggeration, one of the most satisfying monster rampages ever put on film.

The alligator crashes the party. Guests scatter. Cars flip. Politicians scream. Wealthy elites are swallowed whole. This is class warfare with scales.

Another one of Alligator’s greatest unintentional joys is its complete geographic confusion. The movie is set, according to all known information, in Chicago, yet it was filmed largely in Los Angeles. It feels at all times like it’s happening in some vague American city that exists only in monster movies. Then there is the fact that the police vehicles in the film appear to have Missouri license plates.

When the young Marisa returns home with her family from their vacation in Florida, they pass a sign that reads “Welcome to Missouri”. It takes pains to not be St Louis, as this is where the lead character has come from. Landmarks don’t line up. Geography collapses.

Beyond this, sewers connect places they absolutely shouldn’t. The city becomes a dream logic maze where anything can happen, up to and including a 36-foot alligator bursting out of a manhole.

But honestly? This just adds to the charm. This isn’t a real city. This is Monster City, and the zoning laws were written by idiots.

By the time Alligator hit screens, the Jaws knock-off era may have been on its last legs, but Alligator stands tall.

It is meaner, bloodier, and smarter than it had any right to be. It doesn’t try to be Spielberg. It doesn’t pretend it’s elevated. It just delivers the goods. Real gore. Real stakes. Real contempt for authority. Above all, the monster feels genuinely dangerous.

Alligator remains one of the best examples of what happens when a B-movie commits fully to its premise and refuses to apologize. It’s funny. It’s vicious. It’s cynical in all the right ways.

It understands that the scariest monsters aren’t born. They’re ignored by the people we pay to protect us.