Back from the dead… well, our old site. Can a UK production studio like Hammer be part of Hollywood History? Well, they truly were a massive global success. This success was, in part, due to clever distribution partnerships with United Artists, Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, Columbia Pictures, Paramount Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, American International Pictures, and Seven Arts Productions.

Also, Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing remain among the very best interpretations of the famous characters they played in Hammer Horror productions.

So yes, we’ll allow it! Hollywood History returns once more here at Last Movie Outpost. So it is…

Hammer Time

Frequent attempts to help Hammer Films undergo something of a rebirth, with restorations and new movies all planned, started us off reminiscing with you, our Outposters, about the fond memories we all had of Hammer horror growing up.

From buxom serving wenches falling under the spell of an evil vampire Count to a lumbering, reanimated corpse monster on a rampage, all of the memories were fine ones. But how did it all start? And how did it become the veritable monster of monster movies?

It all started in a chilly, grey London back in November 1934. A comedian and businessman William Hinds had the stage name of Will Hammer. He had taken this from the area of London where he lived – Hammersmith.

He registered a film company as Hammer Productions Ltd with its modest headquarters being a three-room office suite at Imperial House, Regent Street, London.

Using his own money with a small group of other investors he started work on The Public Life of Henry the Ninth in leased space at the MGM/ATP studios. On the back of this release, he came to be acquainted with Spanish émigré James Enrique Carreras, a former cinema owner. Together they formed a film distribution company in May 1935 – Exclusive Films.

Under their partnership, Hammer produced The Bank Messenger Mystery (1936), The Mystery of the Mary Celeste (1935 – Phantom Ship in the U.S.) which starred Bela Lugosi, Song of Freedom (1936) featuring Paul Robeson, and Sporting Love (1937).

A strong starting run was brought to a crashing halt by a slowdown in the British film industry which forced Hammer into bankruptcy. Exclusive survived.

Post War

James Carreras re-joined Exclusive in 1946 after demobilization from World War II and took with convened Antony Hinds, William Hind’s son, to rejoin with him. They resurrected Hammer as the film production arm of Exclusive. Their mission was to supply “quota quickies”, cheaply made domestic films designed to fill gaps in cinema schedules and support more expensive features.

Death in High Heels, The Dark Road, and Crime Reporter were followed by movie adaptions of BBC radio series such as The Adventures of PC 49 and Dick Barton: Special Agent.

With a constant eye on budget, the company quickly worked out that renting studios and building sets was expensive. However, the UK was full of old country houses that provided both the space and the look they wanted. So for Dr Morelle – The Case of the Missing Heiress they rented Dial Close, a 23-bedroom mansion beside the River Thames in Maidenhead.

This was such a commercial revelation for them that, eventually, after several changes of venue they were led to Down Place, also by the Thames. In 1951 they acquired the virtually derelict house and remodeled the whole building. It became Bray Studios.

The building itself and the large grounds basically became the setting for so many of their movies that it is recognizable instantly. It provided a key element of the atmosphere in what would become Hammer’s most famous product genre.

The Horror

In 1951, Hammer and Exclusive signed a four-year production and distribution contract with Robert Lippert, an American film producer. The contract meant that Lippert Pictures and Exclusive effectively swapped products for distribution on their respective sides of the Atlantic. One thing Lippert insisted on was an American lead in the Hammer movies he was to distribute and he used his contacts to help Hammer get them.

This arrangement was fantastically successful for Hammer and allowed them to be more adventurous with their movie-making. In 1953, the first of Hammer’s science fiction films, Four Sided Triangle and Spaceways, were released.

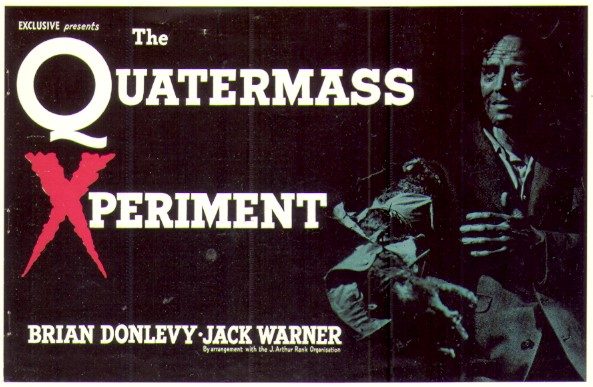

It was by straddling across this genre and horror that they would eventually cross into the subject area for which they would become most famous. A 1955 adaptation of Nigel Kneale’s BBC Television science fiction serial The Quatermass Experiment was directed by Val Guest. The Lippert contract meant American actor Brian Donlevy was imported for the lead role and the title was changed to The Quatermass Xperiment to cash in on the new X certificate for horror films.

The film was a smash hit and led to the 1957 sequel Quatermass 2 and another horror film, X the Unknown.

When submitted to the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) for comment in script form one reader/examiner (Audrey Field) had an attack of the vapors regarding the subject matter. You can almost hear her clutching at her pearls as she wrote:

“Well, no one can say the customers won’t have had their money’s worth by now. In fact, someone will almost certainly have been sick. We must have a great deal more restraint, and much more done by onlookers’ reactions instead of by shots of ‘pulsating obscenity’, hideous scars, hideous sightless faces, etc, etc.

It is keeping on and on in the same vein that makes this script so outrageous. They must take it away and prune.

Before they take it away, however, I think the President [of the BBFC] should read it. I have a stronger stomach than the average (for viewing purposes) and perhaps I ought to be reacting more strongly.”

As the Lippert contract came to an end, Hammer was in no rush to give up on the USA. It sought a new partner to handle the American promotions and eventually settled on Associated Artists Productions (AAP).

Two young American filmmakers, Max J. Rosenberg and Milton Subotsky would later go on to establish Hammer’s rival Amicus. Earlier in their careers, they submitted a script to AAP for an adaptation of the novel Frankenstein. AAP was not prepared to back a movie by producers with just one film to their credit but AAP head Eliot Hyman sent it to Hammer.

History tells us that the script was a mess. Estimated to run at only 55 minutes, and in danger of being a copyright infringement on Universal’s Son Of Frankenstein, it needed attention. Hammer’s Michael Carreras said at the time:

“The script is badly presented. The sets are not marked clearly on the shot headings, neither is DAY or NIGHT specified in a number of cases. The number of set-ups scripted is quite out of proportion to the length of the screenplay, and we suggest that your rewrites are done in master scene form.”

After numerous rewrites, Hammer was eventually persuaded it was good enough for production in full color. The script was submitted to the BBFC and once again Audrey Field had something to say:

“We are concerned about the flavour of this script, which, in its preoccupation with horror and gruesome detail, goes far beyond what we are accustomed to allow even for the ‘X’ category.

I am afraid we can give no assurance that we should be able to pass a film based on the present script and a revised script should be sent us for our comments, in which the overall unpleasantness should be mitigated.”

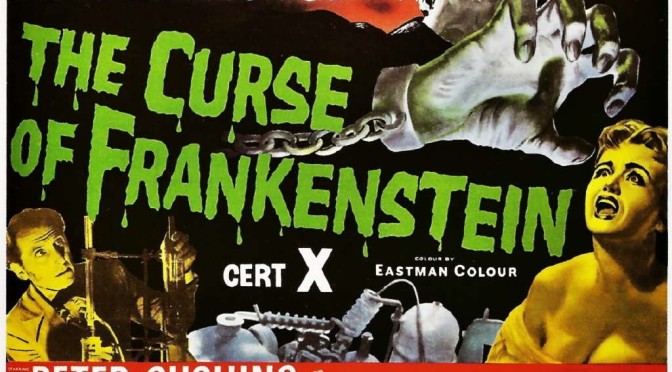

Hammer ignored them and shot the movie unchanged. With a tiny budget of £65,000, Hammer achieved something for which they would become famous, making cheap movies look much, much more expensive. They also uncovered what would become a power couple of stars for them throughout their history.

British TV star Peter Cushing portrayed Baron Victor Frankenstein, with Christopher Lee cast as the Creature. Color encouraged a level of gore, allowing blood to be shown in a graphic way. The movie was a huge success in Great Britain and the US. So much so that famed rip-off artist and Roger Corman and American International Pictures made their own version. Italian directors and audiences were also big fans.

Does this mean it was the first grindhouse movie? Cheap, fast, gory? It could be!

Now firmly embedded in the world of horror, they were about to unleash the biggest of their big hitters.

Taste The Blood Of Dracula

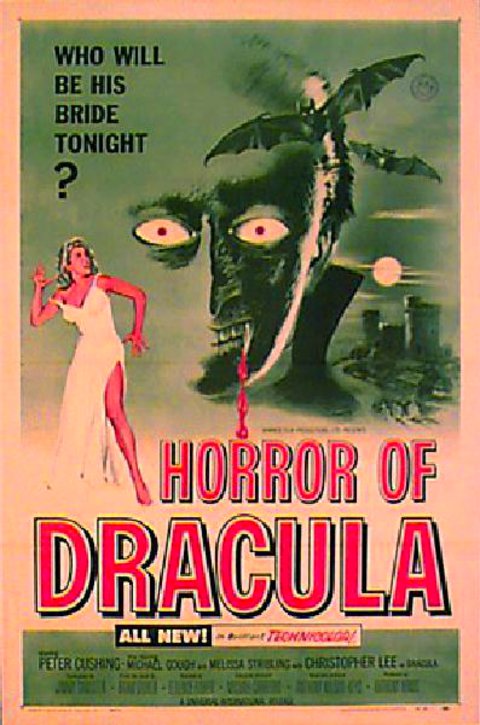

With the box office success of The Curse of Frankenstein giving them direction, Hammer wanted to give their treatment to another horror icon. Dracula, though, had a more complicated copyright situation and required an 80-page legal agreement to be in place between Universal and Hammer. This agreement was not even completed until after Hammer had shot their movie.

Meanwhile, AAP had failed to pay Hammer what they owed, so Hammer pulled the plug on that deal and signed up with Columbia to distribute The Revenge of Frankenstein, The Camp on Blood Island, and The Snorkel.

As part of their preparation for Dracula, they submitted the script to the BBFC once again, where everybody’s favorite censor had even more to say. Audrey Field:

“The uncouth, uneducated, disgusting and vulgar style of Mr Jimmy Sangster cannot quite obscure the remnants of a good horror story, though they do give one the gravest misgivings about treatment. […] The curse of this thing is the Technicolor blood.

why need vampires be messier eaters than anyone else? Certainly strong cautions will be necessary on shots of blood. And of course, some of the stake-work is prohibitive.”

Universal was not interested in financing another version of Dracula and financing was not immediately forthcoming. Eventually, Hammer returned to Eliot Hyman, one-time founder of AAP, through his new Seven Arts company.

From this point on, it all gets a bit messy. The actual funding of Hammer’s Dracula movie is a true cinema mystery. An agreement was reached with Seven Arts, but allegations have been made that the funding was never in place and that the National Film Finance Council stumped up £33,000, with the rest coming from Universal’s payment for the worldwide distribution rights.

However according to some scholars, this is still not conclusive (Barnett – Hammering out a Deal: The Contractual and Commercial Contexts of The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), from the Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 19/3/2013.)

Whoever paid for what, they got Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee back together again and a cinematic legend was made.

It was released in the U.S. as Horror of Dracula and it broke box office records across the world.

Cushing would return to the role of Van Helsing several times, but Lee also would face off against different opposition in subsequent sequels, while some such as The Brides of Dracula did not feature him at all.

One of the hallmarks of the series was finding new ways within the vampire mythos to resurrect and kill the Count each time, from running water, thorns such as those found on the crown of Christ, to the sheer power of faith.

Christopher Lee grew increasingly disillusioned with the direction the character was being taken and with the poor quality of scripts. He would ad-lib at least one line from the original novel into all the movies, except for Dracula: Prince of Darkness where Dracula does not say a word for the entire movie.

Lee famously claims he was appalled by his dialogue so he simply refused to speak it. Others have said that the character was written that way in the sequel.

After filming The Satanic Rites of Dracula he walked away from the role and John Forbes-Robertson took over for the vampire and kung-fu mash-up The Legend Of The Seven Golden Vampires. By the mid-1970s Hammer was done with Count Dracula.

The Slow Death

While incredibly tame by today’s standards, Hammer films always sold themselves on violence, gore, and sex. Now the US was catching up, freed from the overzealous shackles of The Hollywood Production Code they could pitch the same style. Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch showed mainstream audiences plenty of blood, expertly staged Hollywood blood, and violence.

Then George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) came out and changed absolutely everything in the world of cinema gore. Hammer was left without their main USP.

In 1969 Tony Hinds resigned from the Hammer board and retired from the industry. This left Hammer adrift and they tried to up the shocks but failed.

They also attempted to ramp up the sex but again they didn’t make headway. Their party trick had been tapping into the secret, dark desires of a prissy, puritanical America via distribution deals. America was no longer so uptight. Its censorship was relaxed, and its morals forever changed. There was no home for the British curiosity anymore.

Even Dracula was updated with Dracula AD 1972 and The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973) throwing off the period settings and being set in the then modern day. It didn’t work. Under the latter’s working title of Dracula is Dead…and Well and Living in London, Christopher Lee himself said at the time:

“I’m doing it under protest… I think it is fatuous. I can think of twenty adjectives — fatuous, pointless, absurd. It’s not a comedy, but it’s got a comic title. I don’t see the point.”

Lee knew the writing was on the wall and exited the role forever. Investment dried up and eventually, production ceased.

The Hammer House Of Horror

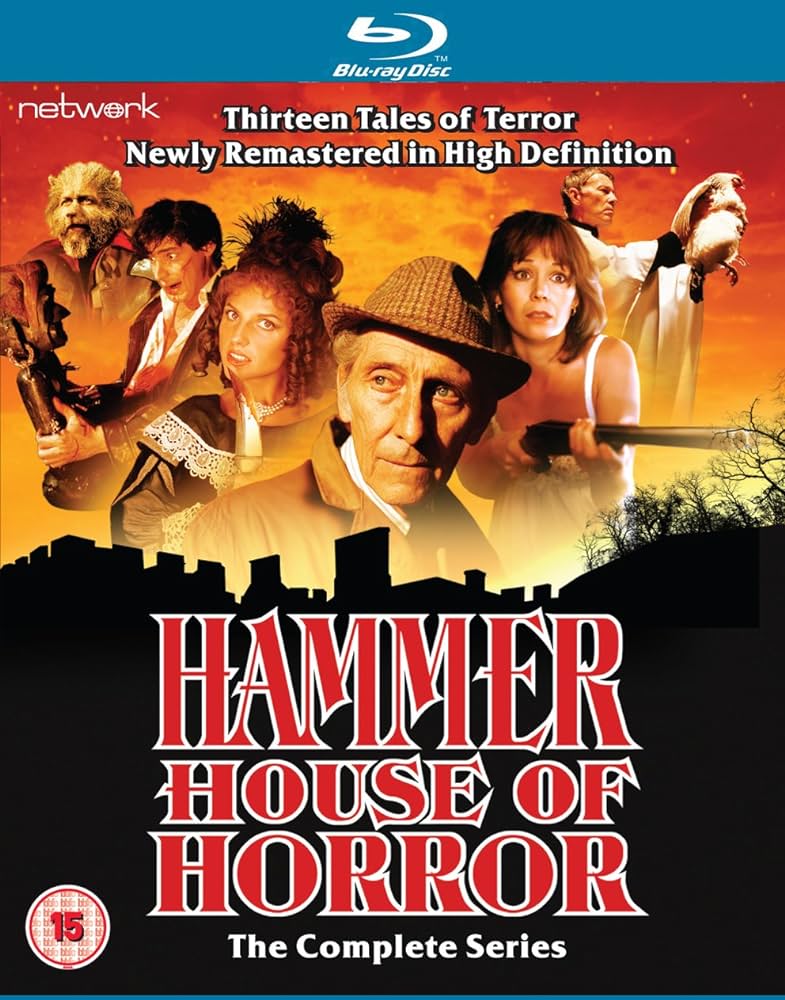

The name still had cachet in the world of horror. No walkthrough of Hammer’s history is complete without mentioning its short extension of life on television. ITC Entertainment created Hammer House of Horror as a television series in 1980.

This anthology series was made by Hammer Films for broadcast on ITV. 13 episodes, each an hour-long, ran the entire breadth of Hammer’s horror toolkit.

There were witches, werewolves, devil-worship, voodoo, poltergeists, cannibals, and serial killers. If you were a certain age in the UK in the 1980s this show was legendary, discussed in hushed tones in school playgrounds. It featured turns from Peter Cushing himself, Diana Dors, Denholm Elliot, Manimal actor Simon MacCorkindale, and even a young Pierce Brosnan.

Many of these episodes are still available online, including on YouTube. Take it from your old pals at Last Movie Outpost and have a search. We recommend them.

Back From The Dead

In 2000 the studio was bought by a consortium including advertising executive Charles Saatchi and his partners Neil Mendoza and William Sieghart, themselves publishing experts. After many false starts, with promises of imminent rebirth, nothing happened until May 2007 when the company name was sold to Dutch media tycoon John de Mol. This included their back catalog of 295 pictures.

Simon Oakes was installed as CEO of the newly relaunched Hammer and said:

“Hammer is a great British brand—we intend to take it back into production and develop its global potential. The brand is still alive but no one has invested in it for a long time.”

A $50 million investment was made allowing them to begin to produce movies once more. One of their first movies was Let Me In (2010), the remake of the 2008 Swedish film Let the Right One In. The film tells the story of a bullied 12-year-old boy who befriends and develops a romantic relationship with a female child vampire. This proves that Hammer will never be too far away from the subject of vampires.

They were also behind The Woman In Black which was an adaptation of Susan Hill’s 1983 novel of the same name starring Daniel Radcliffe, Ciarán Hinds. The story also forms the basis of one of London’s longest-running theater productions of the same name. You can still go and watch it in London today. It contains one of the most simple yet effective scares ever deployed on the stage.

A Lasting Legacy

Horror such as The Phantom Of The Opera and The Devil Rides Out, other non-Dracula vampire movies like Vampire Circus and Kiss Of The Vampire, psychological thrillers like Hysteria and Fanatic, prehistoric adventures like One Million Years BC, swashbucklers like The Men Of Sherwood Forest and The Scarlet Blade, war movies like The Steel Bayonet, comedies like The Anniversary.

Basically, if it could be filmed, Hammer made several of them. It really was the little studio that could, and it has left a permanent mark on global cinema. A true cinema legend.