Having spent Saturday evening rewatching Electric Boogaloo: The Wild Untold Story of Cannon Films and revelling in the sheer insanity of Golan and Globus, I remembered this article so wanted to share it again with our Outposters.

Highly recommend it for a peek at some of the greatest Hollywood insanity there ever was! Hope you enjoy it…

If the movies this studio made were wrong, then I don’t wanna be right. It’s time to talk about…

Cannon Films

This studio managed to simultaneously churn out some of the worst movies known to man and yet, at the same time, completely capture the hearts of movie fans of a certain age. If you grew up in a certain era, the Cannon Films ident at the start of a movie was a welcome sign, both comforting and the harbinger of a damn good time ahead.

How did it manage this? Sure, some of it might have to do with us being young and dumb, with personal quality control issues. Yet there was something else going on at Cannon Films. Something so ruthlessly tactical as to appear almost magical. They didn’t just have their ear to the ground, they had their faces nailed to the zeitgeist.

This also all happened in the greatest era for movie expansion we had ever seen, thanks to a certain invention making its way into every home in the developed world.

How does a movie studio churn out bomb after bomb that are savaged by critics and still soar so high and burn so brightly?

So Wrong, Yet So Right

It started with porn. Yes, seriously.

Cannon Films was incorporated on October 23, 1967 by partners in their early 20s called Dennis Friedland and Chris Dewey. Their immediate income stream came from English-language versions of the Swedish soft porn films of director Joseph W. Sarno such as Inga (1968) and To Ingrid, My Love, Lisa (1968).

By strictly limiting budgets to $300,000 per picture, by 1970 they were off and running with some moderate hits such as Joe, which went on to be Oscar-nominated. However, they failed to build on this strong start and the capital drained away. Changes to film-production tax laws led to a drop in Cannon’s stock price while a string of flops left them ripe for targeting. And targeted they were. By the Go-Go Boys.

Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus were a pair of Israeli cousins who dominated Israel’s film business. They paid $600,000 for Cannon as it was sitting on the US rights for the Golan-directed thriller Operation Thunderbolt. Success with this led them to their business model that would endure for many years. Sequels to existing one-off movies, movies close to other major Hollywood blockbusters, or about a certain craze sweeping the West, or films made by buying bottom-barrel scripts and putting them into production in a hurry.

Tapping into a growing and ravenous market for B movies in the 1980s, primarily driven by the home VHS explosion, the brothers had it made. They had a license to print money.

They put out Death Wish II and were rewarded at the box office. Charles Bronson’s urban vigilante would go on to star in three progressively worse sequels for Cannon. Meanwhile, they combed Hollywood for scripts that aped bigger studio hits, and made them while throttling up the violence and the sex.

On their watch, Fox’s smash teen-sex comedy Porky’s “inspired” The Last American Virgin. Rambo and Red Dawn would become Missing In Action and Invasion USA. Beat Street would get Breakin’ and Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo as cover versions. There was not a trend, craze, or hit that the Go-Go Boys wouldn’t appropriate for Cannon.

During this time, the cousins would voraciously patrol the Cannes Film Festival ready to make a deal with anyone who crossed their paths. The deposits made from these sales financed the production of the first film in the production line-up.

That would then be completed and delivered to theatre owners around the world and made enough money to make the next film, and so on. The Dutch Slavenburg Bank provided bridging loans until the pre-sales cash was collected.

What could possibly go wrong?

The End Of Civilization

By 1983, Cannon was big time. They were making waves in Hollywood and were being noticed. Meanwhile, MGM was running out of product as it entered its downward spiral. MGM signed a deal to distribute some Cannon movies in the US. In turn, this allowed Cannon to snare bigger stars and, supposedly, better scripts. Golan and Globus just couldn’t help themselves, though. Their instincts were just too ingrained and movies were still being rushed into production before they were ready.

So bad was some of this output that MGM chief Frank Yablans described it as:

“The end of civilization as we know it!”

He described the effort Sahara, with Brooke Shields, as a mad mishmash of The Great Race, Lawrence of Arabia, and The Blue Lagoon. John Derek’s soft-core remake of Tarzan, starring his wife Bo with her kit off most of the time was followed by The Wicked Lady.

This remake of a British costume adventure starred Faye Dunaway and is famous for its topless whipping scene. Hercules starring Lou Ferrigno is regarded as having some of the worst special effects in movie history and Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo is described as one of the worst movies ever made. It is so bad, it has got its own cult following.

This led to the collapse of the partnership with MGM. Unbelievably, and probably in testament to Golan and Globus’ deal-making skills, this was not the end of their partnership story. Shortly afterward they somehow managed to snag a deal with another major studio – Warner Bros.

Like the MGM deal, this would allow them bigger budgets and bigger stars. One star who came into their orbit was Sylvester Stallone himself. Stone cold classics of the 80s were the result – Cobra and Over The Top – objectively awful movies but just so much fun we practically ripped them off the shelves at our local video stores. I still have both on VHS today.

By this point, they even owned chains of theatres all over the world. They weren’t just partnering with the big guys though, they made their own movies and this was the golden age for them.

Their military thrillers were a foundation, such as The Delta Force, and Cannon would go on to be a prime driving force in the emergence of the Ninja craze in America through American Ninja, Enter The Ninja, Revenge Of The Ninja, and Ninja III: The Domination. They weren’t shy, and knocked off Raiders of the Lost Ark with a version of King Solomon’s Mines, starring Richard Chamberlain and Sharon Stone.

Drunk on success, Cannon had ideas way above its station and the quality of its product. Golan and Globus wanted to make some big, big moves. Like so much else in the world of movies, these moves would revolve around superheroes.

Low Budget Tights

They had eyes on bigger prizes and invested more and more capital in larger properties. After feeling stung by Superman III, Christopher Reeve was reluctant to return as Superman. In the end, Cannon lured him back through a combination of a huge paycheck and purchasing Reeve’s own terrible story outline about nuclear disarmament.

By the time they had paid out on Reeves and a returning Gene Hackman, with 30 other movies all in development at the same time, Cannon was low on funds. The budget for Superman IV: The Quest for Peace was hacked and slashed.

The resulting movie was such a dud it killed Superman for 20 years on the big screen. Warner Bros. bailed out, taking their money with them, and Cannon found itself drowning in debt that some alleged to be strung out all over the world via a labyrinth of financial arrangements. Cannon wasn’t finished, though.

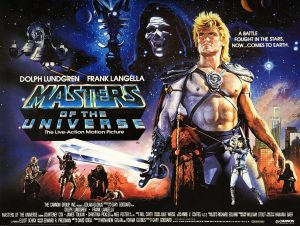

They acquired the rights to several Marvel properties including Captain American and even Spider-Man. They had big plans. They always had big plans. Before they executed them, they had a final roll of the dice to make. Masters Of The Universe.

It was a critical and financial fiasco. Sure, it may be well-loved in an ironic, cult-following kind of way today but you cannot underestimate how much of a stink it made on release. A sprawling sci-fi epic that was very close to the toy line and cartoon, with inspiration from Jack Kirby comics, was the victim of Cannon’s lack of funds and slapdash approach to filmmaking.

Budgets never materialized and the movie was scaled back, re-written and re-worked in the face of this reality.

The substandard product was savaged and it grossed only $17 million worldwide against a budget of $22 million. This was the final straw for the struggling studio that had long had an appetite bigger than its actual stomach could handle. The studio was, at this point, essentially dead in the water. Captain America, starring J.D. Salinger’s son Matt, went straight to video. Spider-Man was never made and the rights, expensively purchased, reverted to Marvel.

Cannon would limp on in various forms, first under the stewardship of Pathe, and then in conjunction with old partners MGM, but the glory days were gone. Attempted relaunches fizzled and eventually, it was killed in a legal battle between new owners and Credit Lyonnaise in a £1.48 billion dispute around Italian financier Giancarlo Parretti.

The Myth And The Legend Of The Go-Go Boys

Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus had exited the business long before that court case, but stories of these two giants of the movie business continued to circulate. Can you imagine a movie studio, and particularly the people who ran it, being so famous for their spirit, their antics, their sheer chutzpah, and even the legend they created being the subject of a movie themselves?

Such was the immense adventurism of Golan and Globus that there isn’t one movie about them. There are two, both released in 2014. Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films was written and directed by Mark Hartley.

An Israeli documentary The Go-Go Boys: The Inside Story of Cannon Films was launched at the Cannes Film Festival the same year. For the full inside story, it is well worth checking out either, or both, of those documentaries.

When researching for this article I was reminded of some of the stories I heard back in the day. These stories seem to have got even better with age.

The casting of Sharon Stone in King Soloman’s Mines perfectly illustrates their slapdash approach and speed of working. When studio chief Golan ordered the casting of “that Stone girl,” he actually meant Kathleen Turner, then fresh off Romancing the Stone.

Nobody knew of the mistake until Golan started viewing the dailies and enquired “Who the hell is that?”

Golan and Globus were known for massively over-hyping their movies. Again the ambition in their heads could not be supported by the reality of their movie making. Lifeforce (1985) was to be “the cinematic sci-fi event of the ’80s” while Masters of the Universe (1987) was dubbed “the Star Wars of the ’80s.”

They were also known for sometimes selling movies that didn’t actually exist. Such was Golan and Globus’ hunger to make a deal that they would make up movies in the heat of negotiation to close the deal. The studio would then have to close the gap.

Stories were made up there and then to fit the titles that the Go-Go boys had just conjured up out at Cannes or around the negotiating table. It’s hard not to dig this approach for its sheer audacity.

When in production, there were no extensions and no additional budget. If a director ran over he was shut down. Footage was turned over to Cannon’s editors who simply did what they could with whatever had been made, regardless of what was missing and no matter if this made a movie incoherent.

Rambo clone Missing In Action, starring studio favorite Chuck Norris, was said to actually be a sequel to an already-shot film that was in the can. That movie was so terrible that it was held back. Missing In Action was then released first with the terrible movie then released as a prequel – Missing in Action 2: The Beginning.

Jean-Luc Godard and Norman Mailer were hired for an ambitious adaption of King Lear via a contract scribbled on a napkin during the Cannes Film Festival. Then director Godard threw out Mailer’s script on the first day of shooting. Mailer, who was also supposed to play Lear, walked out. The result was a barely watchable mess that was tricked out on a limited release.

Classic Golan and Globus!

They did occasionally fly high. Runaway Train grabbed three Oscar nominations and a Palme D’Or.

On losing control of their company they fell out and set up as competitors in the US. The result was two different, competing movies cashing in on the lambada dance craze that opened on the same day. They both bombed.

They did reconcile before Menaham Golan passed away in 2014. Yoram Globus mainly based himself in Israel after Cannon’s fall but in 2015 he sold his Israeli company, Globus Max, and returned to Hollywood with a plan to launch Rebel Way Entertainment, a company with a mission to reconnect young and web-focussed audiences with the traditional theatrical experience.

Outposters of a certain age feel strangely lucky to have had these two titans of a certain kind of cinema in their lives at such a key stage of our movie-going development.

This article was reproduced from our old, now-dead website thanks to the efforts, and resurrection powers, of Shawn Thompson

Do you have an interest in a period of Hollywood History that you want to share with our community of Outposters? If so, reach out at [email protected] and let us know.

Check back every day for movie news and reviews at the Last Movie Outpost