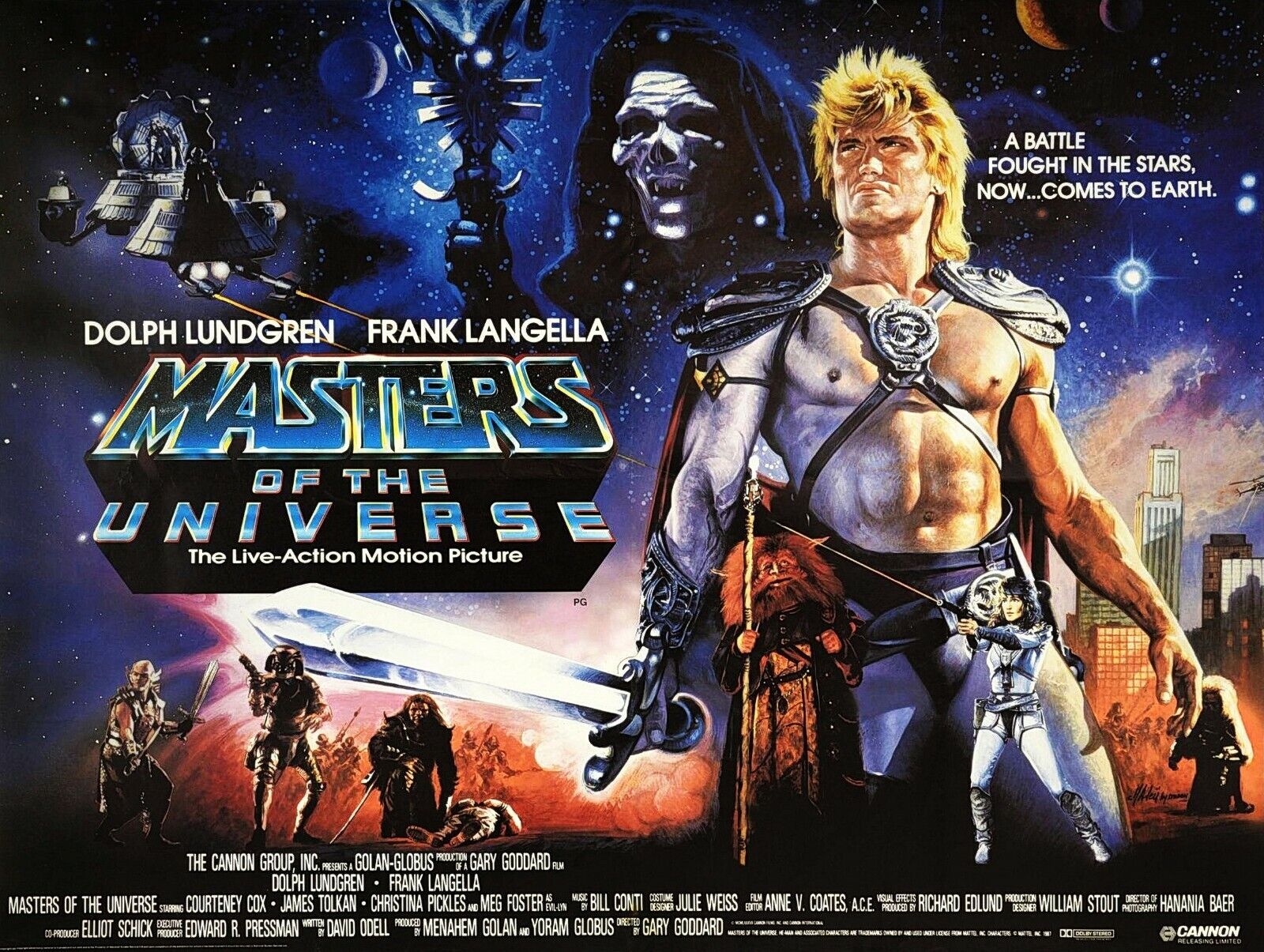

Long before Amazon MGM Studios decided that Masters Of The Universe needed a new live-action reboot movie, those crazy cats at Cannon Films gave us… something.

Some movies arrive fully formed, some arrive confident, resplendent, knowing exactly what they are. The 1987 version of Masters of the Universe arrives like a drunk uncle at Halloween who has been kicked out of a better party up the street, and wanders into yours wearing half a costume, holding a fake prop laser gun, and loudly insisting that everyone look at him.

It is a film born not of vision, but of panic. Panic at Cannon Films. Panic at the box office. Panic that toy sales were peaking. Panic that someone, somewhere, at the studio had already spent the money and now nobody could quite remember where, or on what.

Yet… here we are. Nearly forty years later. Still talking about it. We could all pick the Cosmic Key out of a display of movie memorabilia at the same speed we could identify the Ark of the Covenant. We are still here thinking:

“You know what? It’s not good… but I still kinda love it.”

So, by the power of Cannon’s mounting debts, let’s journey to Eternia but, for budgetary reasons, wind up in suburban America.

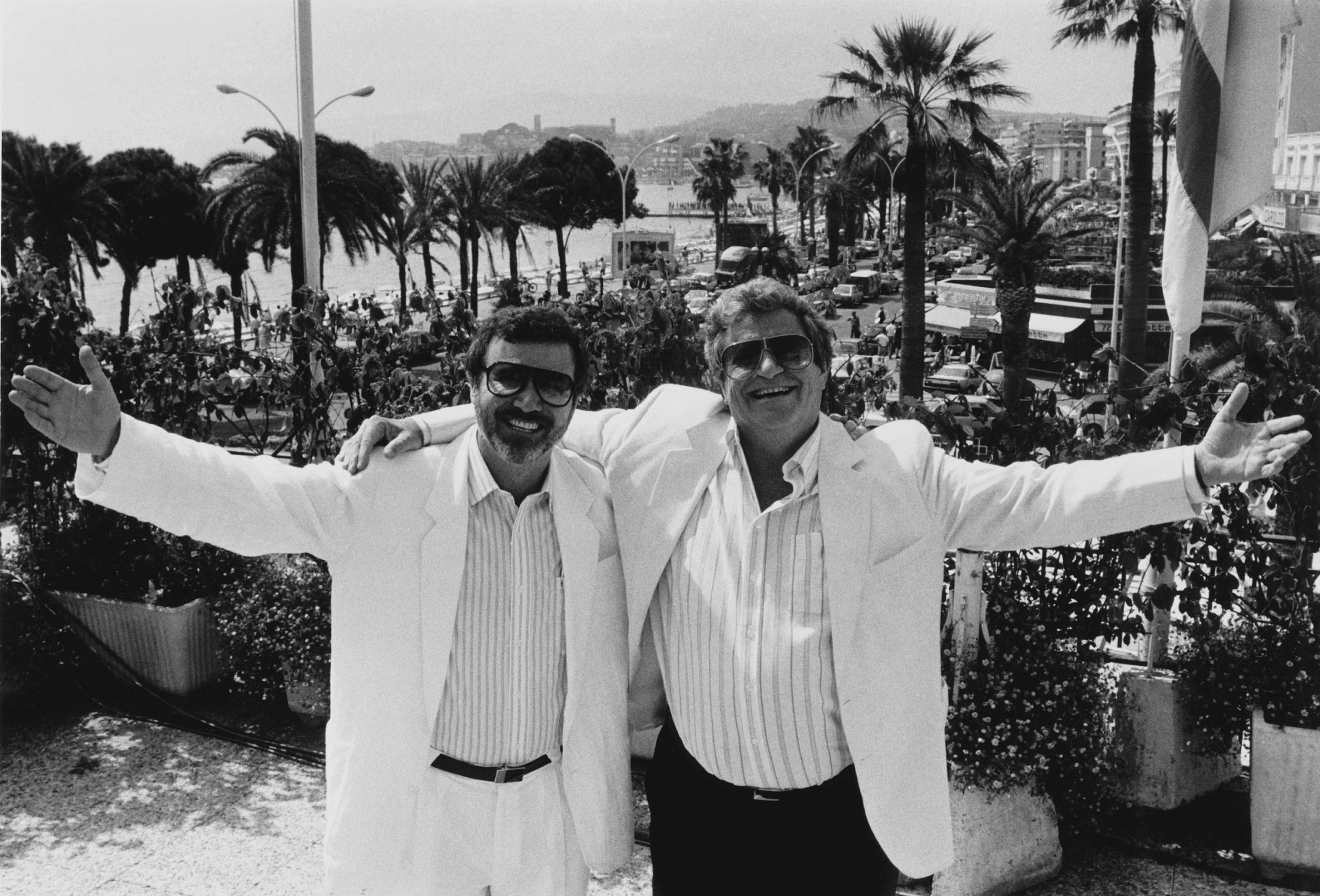

To fully understand Masters of the Universe as both a movie and an artefact, we must first understand Cannon Films in the mid-1980s. A studio run by two men (Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus) who believed that the best way to solve financial problems was to make more movies, faster, and louder.

Cannon didn’t so much greenlight films as release them into the wild. They made everything: ninja movies, Chuck Norris movies, breakdancing movies, sex comedies, prestige projects they didn’t understand, and at least one film that was legally a movie but spiritually an argument.

By 1987, Cannon was wildly overextended. They’d spent huge money chasing legitimacy, culminating in the disaster that was Superman IV: The Quest For Peace. Suddenly, for Cannon, the cashflow was doing that thing where it politely excuses itself and then never comes back.

Masters of the Universe was supposed to be Cannon’s crown jewel. It was to be a massive sci-fi fantasy blockbuster that would turn toy aisles into gold mines and gold mines into solid cocaine. Instead, the budget started shrinking like Skeletor’s dignity.

Originally envisioned as a full-on Eternia-set epic, the film was slowly strangled by reality. Sets were scaled back. Effects were simplified. Scripts were rewritten on the fly. Eventually, someone said the fateful words that doomed the movie to VHS immortality:

“What if… he comes to Earth?”

This was not a creative decision. It was an accounting decision. So welcome to Eternia, now please enjoy this High School assembly hall.

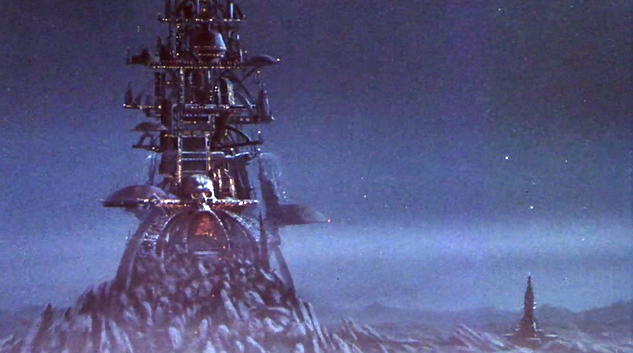

If you are of a certain age, and you grew up with the adventures of He-Man, you will remember Eternia as a place of impossible colors, endless castles, and villains who looked like they were designed by someone aggressively unemployed.

In the movie, we get Eternia for about six minutes, during which we see Castle Grayskull, some rocks, and the overworked smoke machine straight off the set of Ninja III: The Domination. Skeletor is already winning, when suddenly we are whisked away to Earth because Earth is cheap. Earth has streets. Earth has walls. Earth has police cars you can rent by the hour. Earth does not require building an entire alien civilization from scratch, while Cannon’s creditors bang on the door demanding you stop making this film.

So instead of epic fantasy, we get Dolph Lundgren wandering around small-town America dressed like a shirtless Viking, asking teenagers for help like he’s lost his car at the mall. It’s jarring. It’s awkward. It’s clearly a compromise.

And honestly? It kinda works… in the way that a broken thing can still be weirdly charming.

Lots of this is down to Dolph Lundgren. He’s like He-Man, only quiet. Lundgren looks like the perfect as He-Man. Uncannily perfect. If Mattel had grown a man in a lab and taught him to flex, this would be the result. But he barely talks.

When he does, he sounds like English is his third favorite language, after Swedish and punching.

He-Man in the cartoon was a confident, moralizing space barbarian who loved explaining lessons. Movie He-Man looks like he’s thinking very hard about whether doors are his natural enemy.

Still, there’s something endearing about Lundgren’s performance. He’s sincere. He’s not winking at the camera. He’s not embarrassed. He’s playing it straight, even when firing laser guns at guys dressed like they lost a bet at a sci-fi convention. You believe that he believes in this nonsense, and that counts for something.

Meanwhile, Orko also died for accountancy.

The floating, wisecracking wizard from the cartoon was deemed too expensive and too effects-heavy. So Cannon did what they had to do – they invented a new character nobody asked for. A small, furry, trumpet-nosed creature called Gwildor, who looks like a rejected Ewok and exists primarily to hold the plot together with duct tape. Gwildor replaces Orko as comic relief and exposition machine, and he really tries, but it’s not his fault.

Gwildor did nothing wrong. Gwildor was born of financial necessity and raised by compromise, but for a generation of kids expecting Orko, Gwildor felt like betrayal wrapped in foam prothetics.

On the upside of all of this is Frank Langella, who manages to act in the wrong movie and still win. Langella as Skeletor is too good for this movie. Not “better than expected.” Not “surprisingly solid.” He is operating on an entirely different artistic plane.

Langella’s Skeletor is theatrical, venomous, operatic. He chews scenery like it is made out of sugar and he’s a type 1 diabetic. He doesn’t snarl, he enunciates. He doesn’t rant, he performs. Every line delivery feels like it wandered in from a Royal Shakespeare Company production happening two soundstages over, and nobody thought to stop him.

Why did he take the role? Because his young son loved He-Man. That’s it. That’s the reason. No irony. No cynicism. He did it out of love.

Because of that, Skeletor becomes the best thing in the movie by a country mile. When Langella delivers his monologue about power and eternity, it’s genuinely compelling. He is magnificent. The movie does not deserve him. We are grateful anyway.

Alongside him is Meg Foster, and she is… a lot for a teenage boy to handle. Her voice is cool. Her stare is hypnotic, like a cobra hypnotising a chicken, and her costume is doing things a PG movie probably shouldn’t be allowed to do.

For many young boys watching this film, Evil-Lyn was a moment. A strange, formative moment. One where you didn’t yet understand why you felt the way you did, only that something important had happened and you might need a minute alone. She’s menacing, sarcastic, stylish, and somehow sexy.

I don’t, for a second, imagine that Cannon actually knew what they were doing here, but they do it anyway.

So, overall, we are left with a flawed relic, marinated in our own nostalgia. Masters of the Universe is not a good movie. It’s clumsy. It’s compromised. It’s visibly fighting its own limitations at every turn. You can practically hear the producers yelling, “Can we afford that?” off-screen.

And yet…

There’s ambition here. There’s sincerity. There’s a sense that everyone involved – actors, designers, composers – was trying to make something special, even as the ground collapsed beneath them.

This movie exists because Cannon Films was collapsing, because toy empires were fading, because the 1980s believed harder and louder was always better. It’s basically Desperation: The Movie filtered through childhood memory.

We remember it fondly not because it was great, but because it tried. Because it felt big when we were small. And honestly? That’s more than Cannon ever managed with its balance sheets.