No matter how hard I am trying to quit this 80s kick, the state of current movies is really not helping. Every time I sit down and consider something new, I scroll through pages of absolute dross. Then my Amazon Prime Video algorithm, which seems to know me better than any woman I have ever had in my life, sidles up to me and says, “You might like…”.

And, Godammit, it really knows what I might like. It knows I might like things like Road House.

If someone ever asks you, “What exactly was the 1980s?” you don’t need to hand them a documentary, try and describe synthwave, or talk about cocaine-fueled boardrooms full of men with creatively blow-dried hair.

No, no. Just hand them a DVD of Road House. If they don’t get it after that, they’re either dead, German, or some combination of the two.

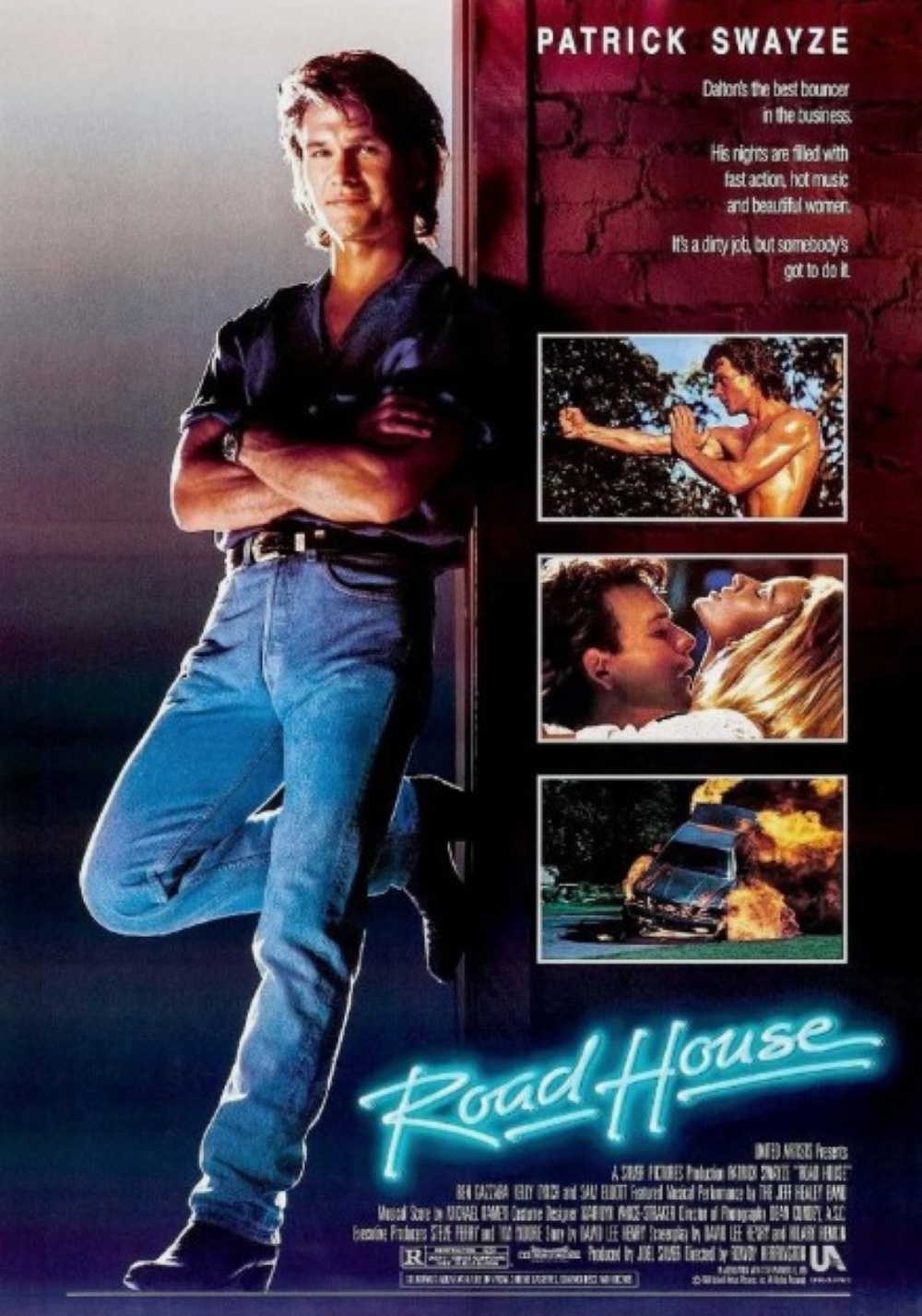

Road House – The 80s, Distilled

Road House isn’t just a movie. It’s an experience. A lifestyle. A Zen koan wrapped in denim, mullets, and the sweet sound of bones breaking. It’s not “so bad it’s good,” because that phrase implies a lack of intention. Road House knows exactly what it’s doing. The only question we’re left with, 35 years later, is:

…was everyone in on the joke, or are we the punchline?

Because Road House is nothing short of sheer 80s awesomeness – pure, uncut, unfiltered, and served straight into your eyeballs.

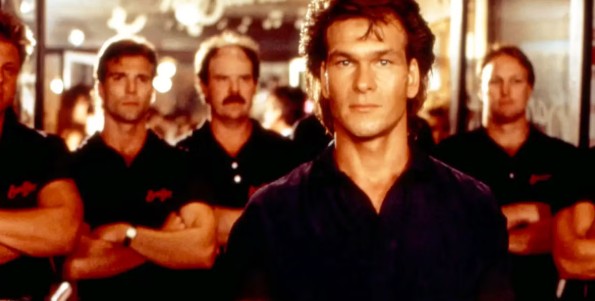

This whole show would be for nothing without Patrick Swayze as Dalton, philosophical bouncer, ballet ninja, and denim prophet.

Swayze had bounced around movies for a while, with roles in things like The Outsiders, Red Dawn, and Youngblood, but he went massive with Dirty Dancing. This was about to herald his hitting the big time. He would star in Road House and Next Of Kin in the same year, before Ghost and then Point Break.

Swayze made every woman swoon, every man question whether they should take up Tai Chi, and every pair of jeans consider early retirement.

Here he plays the world’s greatest bouncer. Yes, you read that right. In a filmography that featured, until then, his biggest role being a dancer, this movie featured Swayze fully committing to playing The Coolest Man Alive. He’s not a vigilante, not a cop, not a mercenary. He’s a professional cooler, which, as far as this movie tells us, is basically a bouncer with a master’s degree and the soul of a wandering samurai.

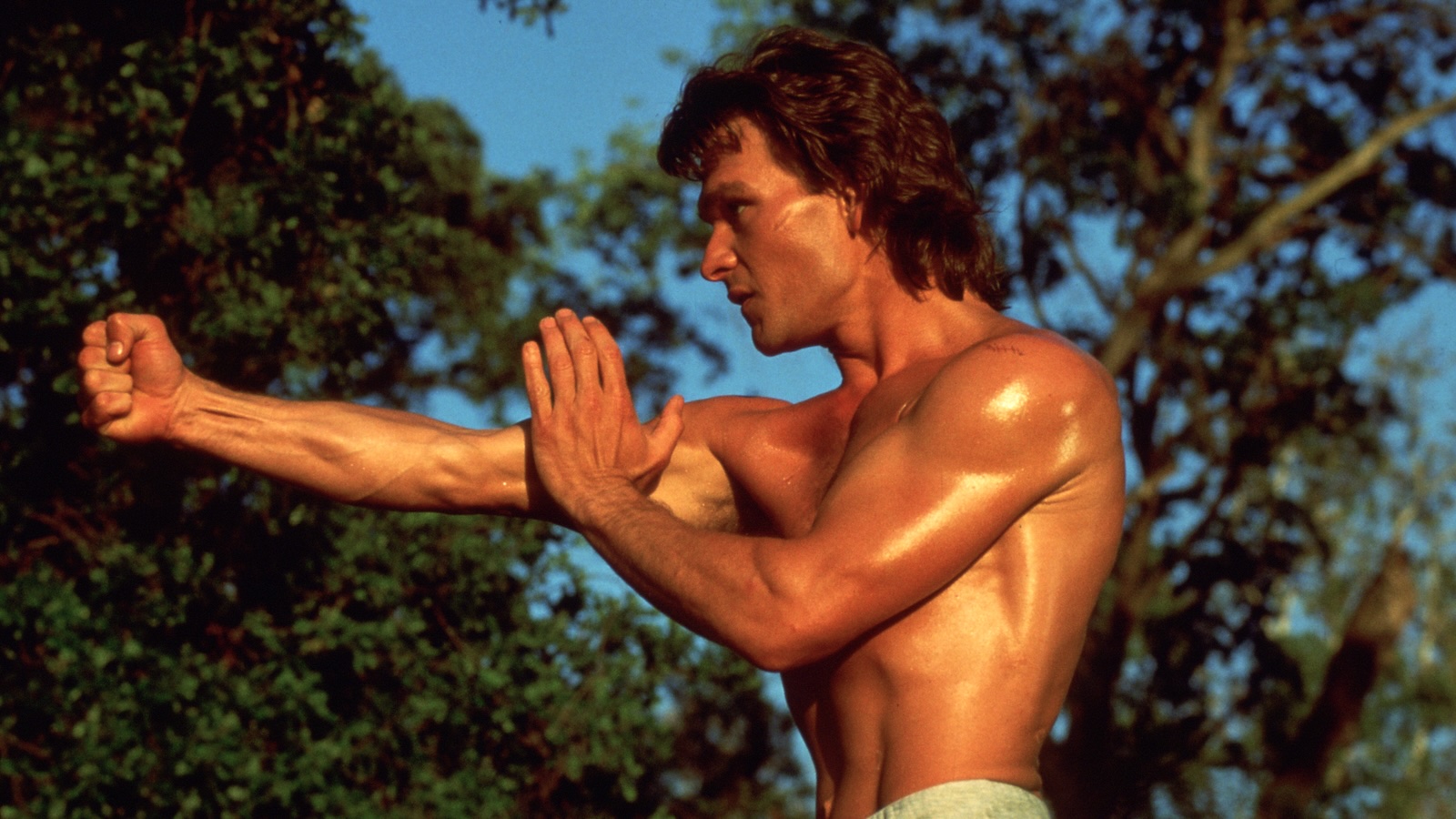

He is introduced reading philosophy like a grad student, but instead of sipping black coffee, he sips black coffee and rips out people’s throats. He wears mom jeans so tight they could qualify for zoning regulations. He practices tai chi in front of sweating, confused farmers at sunrise.

He himself perspires more than a televangelist caught with an underage hooker. And above all else, he delivers some of cinema’s greatest accidental comedy with lines like:

“Pain don’t hurt.”

Cod-philosophy? Sure. Deep? Maybe. Stupid? Definitely. But Swayze sells it. He sells it so hard that every time he says something vaguely Eastern and pseudo-spiritual, you kind of believe him.

Swayze could have said, “Suffering is merely weakness evacuating the soul through the pores of time,” and audiences would have nodded sagely and wondered how to spell “daltonism.”

Whiter Than White

Dalton cuts a swathe through Jasper, Missouri. This town is so white, it could be a ski resort or a yacht club.

Not only is everybody white, but everyone is angry, everyone owns a truck, almost everyone is somehow in shape despite eating 19 pounds of beef per day, and everyone is ready to throw down at the slightest possible provocation.

Did I mention how white it is? This is a town so white that Wonder Bread looks at it enviously. A town where diversity is defined by whether someone likes country rock or blues rock. A town where the local economy seems to be made entirely of honky-tonk bar tabs, monster trucks, and medical bills.

This idyllic vortex of bar fights, bad decisions, and 80s moral clarity needs Dalton, a man who teaches bar employees to be nice while simultaneously breaking more bones than an orthopedic surgeon given nothing but a hammer.

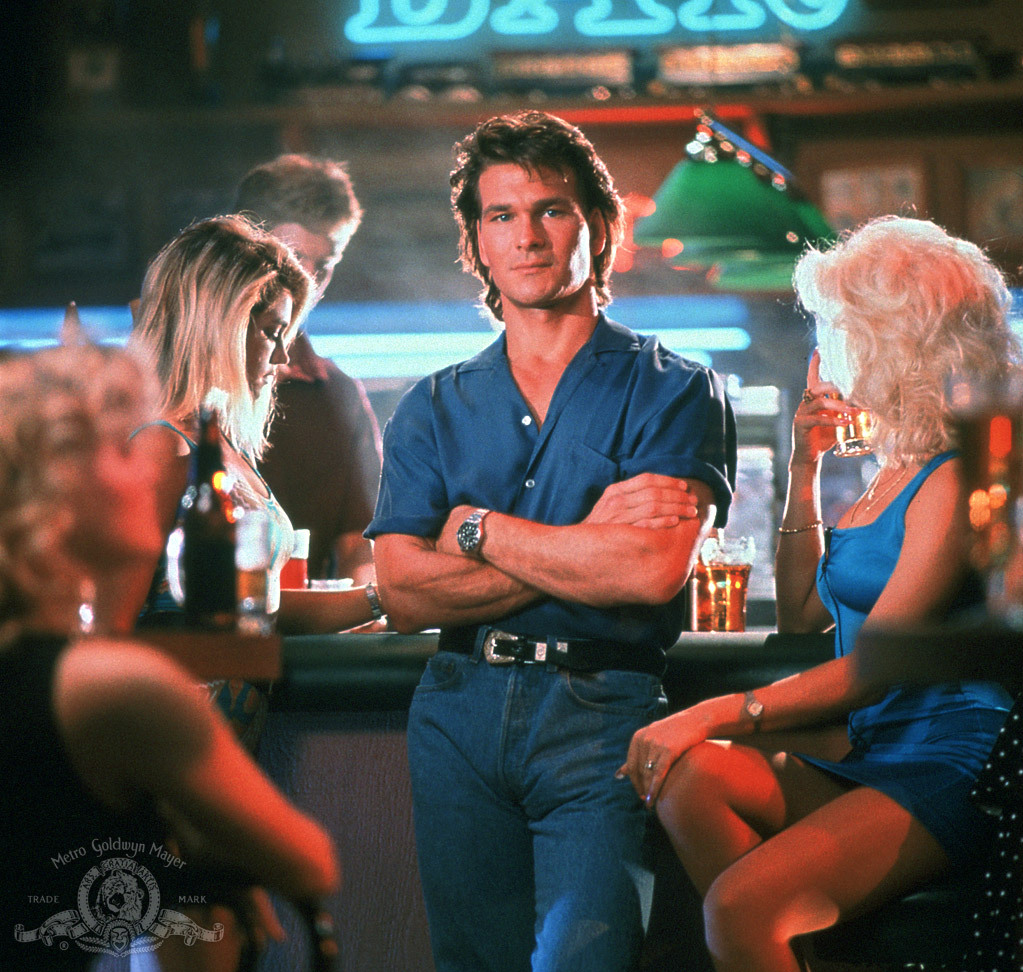

Dalton arrives at the Double Deuce, a bar so rough it makes the Mos Eisley cantina look like a Starbucks. Dalton arrives to find that the Double Deuce is basically a drunken brawl with a jukebox attached, where knives come free with every beer, and ladies flash their boobs with the same frequency normal people check their phones today.

Seriously, this movie treats exposed breasts like background decoration. It’s like the director told the extras:

“If you don’t know what to do, take your top off.”

I’m not complaining. This is the 80s. Subtlety was illegal, and every movie had to feature, by law, a scene set in a strip club. Dalton starts to whip it into shape with just three rules:

Be nice.

Be nice.

And be nice until it’s time to not be nice.

And the Double Deuce, slowly but surely, evolves from a bar where someone might bleed out on peanut shells to a bar where someone might bleed out on newly varnished hardwood floors. This is progress.

The Cardigan Kingpin

Ben Gazzara plays Brad Wesley, the corrupt local rich guy who runs Jasper like his personal Monopoly board. Wesley looks like the kind of man who owns more golf clubs than guns. He looks like the kind of guy who drinks room-temperature sherry and gets excited about a new line of loafers. He looks like he should be chairman of the HOA, not the overlord of all crime in Missouri.

But somehow – miraculously – Gazzara is absolutely awesome as a villain.

He’s this perfect blend of charming psychopath and suburban dad energy. He flies helicopters low over Dalton’s barn for no reason. He randomly employs a gay prison ninja. He drives a convertible while listening to Sh-Boom at a volume only a sociopath could enjoy. He laughs at his own jokes like a man who’s never been told “no” in his life.

Despite the middle manager at an insurance company aesthetic, he radiates menace like nobody else. When he smirks, you know someone’s about to get run over by a monster truck or mauled by a guy named Jimmy. Speaking of…

Jimmy, Dalton’s arch-nemesis, is the proud owner of one of cinema’s greatest lines:

“I used to fuck guys like you in prison!”

There are threats, there are insults, and then there’s… whatever the hell that is. It’s somewhere between a confession, a compliment, and a cry for help. But in the world of Road House, it’s just another Tuesday and an invitation to a fight.

Jimmy also has the distinction of dying via throat-rip, which is a special martial arts move invented by screenwriters who were definitely drunk. This scene is magnificent. Dalton grabs his throat, tears something important yet undefined out, then looks about as remorseful as a diner who realizes they just used the wrong salad fork.

Thrown into this chaos is Sam Elliott, playing a role like some kind of sexy Gandalf.

Wade Garrett is the grizzled mentor, the original cooler, and the man who makes arthritis charming. His voice is so deep it causes local seismologists to panic. His hair flows like a silver river of manliness. He calls Dalton “mijo” like he’s a cowboy Tío Ben, while he fights with the ease of a man who’s been kicking ass since the Eisenhower administration.

When he arrives in the movie, Road House instantly gains an extra 20 pounds of pure cinematic testosterone. If the movie were a sandwich, Sam Elliott is the thick-cut bacon.

All these characters, and indeed the whole of Road House, is that everyone fully understands that fighting is the first language. Nobody needs an excuse to fight. No provocation required. You could bump into someone, sneeze near someone, look at someone, or be located within a 40-mile radius of someone and… BOOM! Instant bar fight.

And the fights are beautiful. The choreography is 80s perfection: big swings, big kicks, and the kind of sound effects usually reserved for Batman comics. This all centers on the athleticism of Swayze, who moves like a ballet dancer that’s been fed nothing but whey protein and righteous fury.

All of this is powered by dialogue that contains instant quotability. Road House is a quote machine of a movie. It is what would have happened to all of the English language if Shakespeare was born in the Midwest and liked beer and punching people.

A Movie So Great It Transcends Logic

Road House isn’t just great – it’s great in every way. It’s the cinematic equivalent of eating an entire cheesecake with your bare hands while someone plays a keytar solo next to you. It’s the perfect storm of 80s excess, sweaty machismo, and earnest sincerity.

It’s a movie that believes in itself so hard that you believe in it, too.

Is everyone in on the joke? Maybe. Maybe not. But by the time the credits roll, it doesn’t matter. Because you’re too busy quoting lines, humming the soundtrack, and wondering if you should take up kicking tree trunks as a workout.

Road House is a masterpiece. A glorious, ridiculous, denim-wrapped masterpiece.

So be nice. Until it’s time to not be nice.