Another Outposter contribution? Mhatt is like some kind of review machine! Here he is with a Retro Review of a critical darling – Leaving Las Vegas.

Leaving Las Vegas

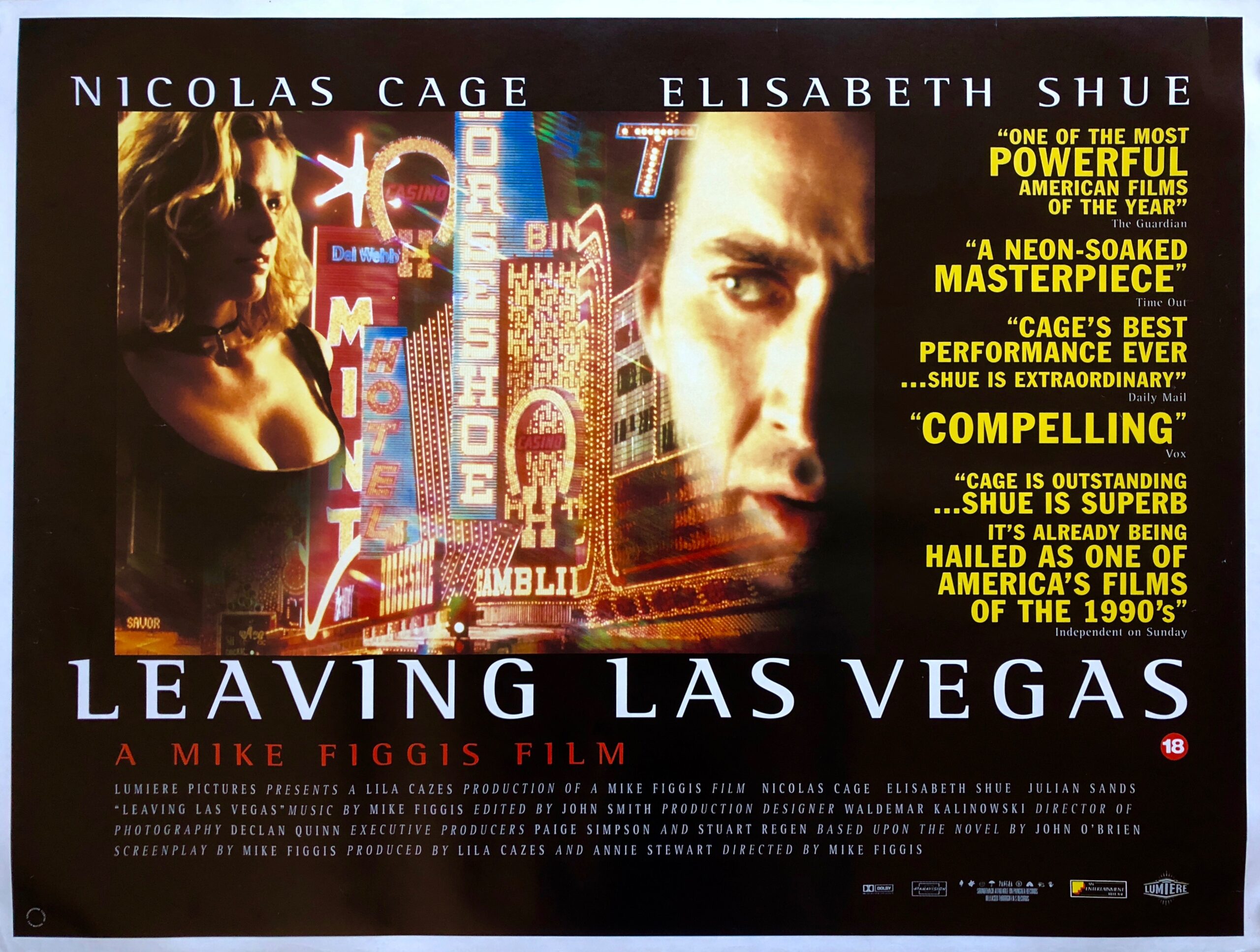

Directed by: Mike Figgis Written by: Mike Figgis based on the novel by John O’Brien.

Cast: Nicholas Cage, Elisabeth Shue, Julian Sands, Laurie Metcalf and Mariska Hargitay.

As the holiday season barrels down on us, I have been thinking about how the rules of polite society are slightly altered all in the name of celebration. The most flexible of these is the consumption of alcohol and its status as a habit of the holiday.

It makes us feel festive; it’s the grease of celebration, the necessity of toasts, the numbing agent that both gives us tolerance and the confidence to make it through one more family gathering without violence.

A drunk person’s mouth is a sober person’s mind, so they say, and with that in mind, I turn to perhaps one of the rawest depictions of alcoholism laid down on film in 1995’s Leaving Las Vegas.

The Plot:

The only thing pretty about this movie is how straightforward the story is; screenwriter Ben Sanderson (Cage) has, somehow at last, drunk himself out of Hollywood after boozing away his wife and child.

He decides to liquidate his assets and then himself in Las Vegas by completely succumbing to his alcoholism. He runs into, almost literally, Sera (Shue), a strip prostitute trying to twist away from a troubled pimp who allies with Ben on his road to ruin.

Performances:

Leaving Las Vegas is a key piece to the puzzle that is Nicolas Cage. An episode of the Dan Harmon show Community tries to determine whether or not Cage is a good or bad actor; here’s the clip:

As far as I’m concerned, this remains the definitive statement on the matter.

Although he’s returned to moderate levels of respectability in the past few years, in the 90s, Nic Cage was the man with too many hits to name here. If nothing else, Cage is usually an interesting actor to watch and always puts a special kind of effort into his roles, bringing a little something you haven’t seen before.

He won a Golden Globe, the SAG, and the Best Actor Oscar for his role in Leaving Las Vegas and was nominated for pretty much every other award that year. As well as visiting hospitalized alcoholics, Cage researched by binge drinking and videotaping himself speaking in order to study his speech patterns and it paid off. He looks like a drunk; you believe him as someone who gets deep into alcoholism without any interference because he’s genuinely likable, but it’s just that he’s got this condition.

The kind of pitiful but fascinating drunk you would cross the street to avoid a chance of being recognized by, but once safe, are too curious not to want to follow.

An existence summed up in a pathetic confession to a hooker as she sucks the wedding ring and the last connection to his past off his finger:

“I’m not sure if I started drinking because my wife left me or my wife left me because I started drinking, but fuck it anyway.”

The novel confirms it was the latter, but as far as the movie is concerned, the past is the past, and the future is booze. No one is going to call Ben Sanderson a hero, but he definitely answered the call to adventure; his layoff was the crossing of the threshold, his call to duty, and we are almost rooting for him to do it.

Elisabeth Shue turned a lot of heads with this role and was duly recognized with a nomination for Best Actress Oscar; she lost to Susan Sarandon for Dead Man Walking.

She plays Sera all over the court, convincingly volleying between strong and extremely vulnerable, a kind woman straddling the flimsy barrier between a superficial ‘stays in Vegas’ experience or a soul-polluting nightmare fueled by addiction and despair.

The only deviation from the spiraling narrative are the cutaways where Sera therapizes with an offscreen entity, these were actually recorded during wardrobe tests, and you can see her reading off the script. Though tough and successful while she had a pimp behind her, without someone to answer to, her purpose becomes uncertain. After all, Las Vegas is a multi-purpose town; some come to experience some amnesiac fun, others come for business, and while killing time between seminars, take none too kindly to offers of professional company.

Maybe it was bad luck, bad timing, or maybe her pimp wasn’t entirely without value that things spun dangerously out of her control, but the difference between her rock bottom and Ben’s was that she bounced. Despite her climactic profession of love to the worst boyfriend possible, what actually drew her to Ben is more or less left up to interpretation.

Ben’s slobbering enthusiasm toward dying provided her with a carefree test drive of her vulnerability, giving her time to grow emotionally and eventually realizing love and need can be exclusive infatuations.

Shue did her own research by interviewing Las Vegas prostitutes and credits the short shooting schedule with allowing her to stay in that particular emotional zone. An experience she looks back on fondly as:

“…a kind of calmness that I felt each day, because if you’re that close to your emotions, there’s a certain honesty that you’re living each day and it, and I miss the film for that reason; we spend so much time of our life trying to be happy and it’s nice to go through an experience like that where you really just get to feel those deeper emotions consistently.”

I’ve never acted, but this seems like an interesting and therapeutic aspect of the craft. I guess if it were just all about the pay cheque there would be far less community theater.

The Direction:

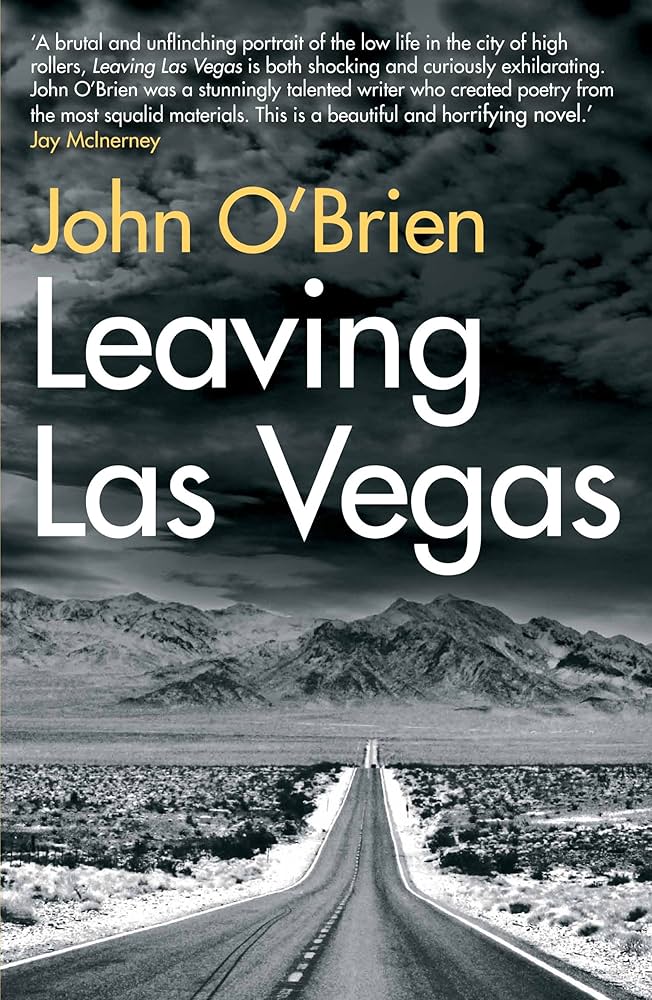

Although it was based on a semi-autobiographical book, Leaving Las Vegas is Mike Figgis’s biography of a very lost man. I do feel a bit of appreciation for the author is due; John O’Brien wrote four novels and, under the pseudonym Carroll Mine, wrote 37 episodes of the Rugrats cartoon. A process that disgusted him due to the editorial changes to his scripts.

After learning Leaving Las Vegas was being made into a film, he killed himself.

His father considers the book to be his suicide note. The film proceeded to be shot on a shoestring budget in twenty-eight days, which allowed the grime and gaudiness of Vegas to stand as a very believable environment where someone on a booze-soaked suicide run could easily succeed.

Gritty looking, often a result of not always having permits and needing to resort to more guerilla-style filmmaking, Figgis delivers a sad portrait of a town that allows you adequate rope to hang yourself with as long as you don’t somehow spook the high rollers.

The film is dotted with the sort of scenes that, instead of chokes of pity, elicit either chuckles or guffaws because that’s what Ben does, and even if we can’t comprehend his demons, we like Ben. Figgis uses some overt visual cues to help immerse us in the relentlessly bleak narrative. Thematically supporting the ring thief scene is when Ben checks into a motel called The Whole Year Inn, which we see through his P.O.V. as The Hole You’re In, and again when Ben falls in the pool and stays submerged, continuing to chug whiskey.

Supporting the visuals is the haunting score, which was composed by Figgis, who plays trumpet and keyboards on the soundtrack, where he also enlisted Sting for three songs. Riveting, sad, and jarring, it beautifully sets the consistently uncomfortable tone as we follow Ben’s perpetual tiptoe along the edge of his inevitable collapse.

It seems like a stroke of compassionate genius that Figgis peppered the cast with famous cameos, which help to remind us a fairer world does exist beyond all this darkness.

In close to order of appearance, we see Richard Lewis & Steven Weber (agents), Emily Procter (wannabe actress), Valeria Golani (bar patron), French Stewart (businessman), R. Lee Ermey (not a John), Julian Lennon (bartender), Danny Huston (bartender), Xander Berkeley & Lou Rawls (cab drivers) and even Mike Figgis himself as a mobster.

Final thoughts:

Genuine drunks aren’t the focus of a lot of movies that I am familiar with, and it is watching Ben Sanderson’s experiences that makes that okay. The only other movie that comes to mind is Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend (1945), starring Ray Milland, which also featured a profound score, evocative of too many late nights and one or several too many drinks, and the desperately futile search for an undefinable contentment that inspires the addict.

The Lost Weekend score was groundbreaking in introducing the Theremin sound, later popularized by too many science fiction movies to name:

So remember, darlings, imbibe wisely; may your holidays be merry and every wish come true, and may you always be remembered as the adult who didn’t embarrass themselves at dinner this year.