Everyone loves a massive, sprawling epic, but things are getting out of hand. It’s not just you. Movies really are getting bigger.

The most recent Bond movie, No Time To Die, was also the longest in franchise history at 2 hours and 43 minutes. The latest Indiana Jones was 2 hours and 23 minutes. Mission: Impossible: Dead Reckoning was 2 hours and 45 minutes long, nearly an hour longer than the first installment in the franchise was. Avatar: The Way Of Water was a butt-numbing 3 hours and 20 minutes. John Wick 4 clocked in at 2 hours and 49 minutes.

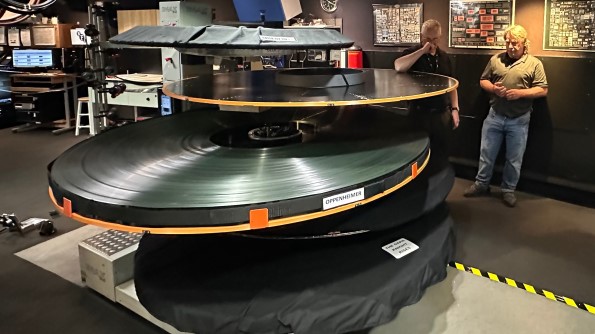

What the hell is going on? Oppenheimer was so big that the IMAX version was 11 miles (18km) long! Luckily, Last Movie Outpost is a much higher-brow place than you might think, and some of us read The Economist.

They published an article looking into this phenomenon, and their analysis showed that since Hollywood’s Golden Age in the 1930s, the average length of a movie has increased by a staggering 32%. The average was 1 hour and 21 minutes back in the 1930s, and now it is 1 hour and 47 minutes. Over 100,000 internationally released movies served as the data source.

Movies are now so sprawling and lengthy that, even at Cannes, audience members fell asleep during the screening of Scorsese’s Killers Of The Flower Moon. All 3 and a half hours of it.

Huge epics like Lawrence Of Arabia and Cleopatra were necessary to establish dominance over television. Back then projectionists would change reels halfway through, giving movie-goers and intermission. However, they were exceptions.

Movies have always been long in the most industrious movie-producing nation on Earth, India. There, they make more movies per year than Hollywood, Europe, and China combined and sell tickets in volumes that a Hollywood executive would give up cocaine for. Three-hour runtimes have been normal in India for decades. But as the normal in the West? It is a fairly recent phenomenon.

According to The Economist, a big driver of this is similar to the reason why those original epics existed. A need to do something big in order to tempt audiences off their sofas and away from streaming, back into theaters.

Big franchises are another driver. Studios want to squeeze the most value out of their costly intellectual property. With streamers taking a bite, they need these spectacular event movies. However long movies cause another challenge. You can only squeeze in two showings per screen, per night rather than the usual three. So it could be a false economy.

The article also points to the rise of a new generation of auteur director who has enough influence to tall the studios to take a hike over running times, and to let their stories breathe, such as Nolan and Scorsese.

Whatever, the cause, the age of the blockbuster has ended. The age of the bladderbuster is clearly upon us.

Check back every day for movie news and reviews at the Last Movie Outpost