Hollywood History is back at Last Movie Outpost. This time, once more from the wreckage, we look at a genre that has been around for longer than we might think, and still has the potential to grab the attention and the imagination of audiences – the Disaster movie.

The Anatomy Of A Disaster

So what makes a disaster movie? A disaster film or disaster movie is a film genre that has an impending or ongoing disaster as its subject and primary plot device. You name it, if it breaks big stuff real good then it can usually be the subject of a disaster movie.

Natural disasters, accidents, military or terrorist attacks, global catastrophes. Even, you could argue, rampaging beasts and alien invasions can contribute to the genre. They usually follow a fairly singular template too.

A degree of build-up, the disaster itself, and then the aftermath, usually from the point of view of specific individual characters, or their families, portraying the fight for survival of different people.

The very best will feature a large, ensemble cast and have multiple plot lines, focusing on the characters’ attempts to avert, escape or cope with the disaster and its aftermath. The character will usually be confronted with human weaknesses, such as falling in love, and there is almost always a villain to blame. This villain will frequently be either a skeptic who argued that the event could never happen, or somebody who has caused the disaster such as a building magnate cutting corners, or a politician cutting costs.

The movie will center on a persevering hero, seemingly played by Charlton Heston in every other movie, and he will be called upon to lead the struggle against the threat, and the fight to survive. In many cases, the villain or other characters portrayed as evil or selfish will succumb to the disaster, a victim of their own actions or hubris.

We all know the rules. The template. But how did we get here?

Humble Beginnings

The moment film was invented, others were finding thrilling things to capture upon it. And what is more thrilling than peril? Fire! (1901) made by James Williamson of England is widely considered the first entry in the genre. The silent reel showed firemen arriving to rescue the inhabitants of a burning house.

The genre got a boost in 1912 when the Titanic sank. Suddenly Titanic-based reels were everywhere. The most famous of these at the time was In Nacht und Eis (In Night And Ice). The 1912 reel was a German interpretation of the sinking of the great ocean liner. This was followed in 1913 by Atlantis, also covering the sinking.

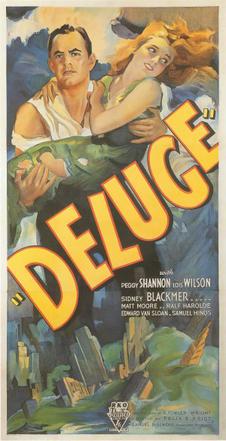

Watery disaster proved a hit and Noah’s Ark followed in 1928 to tell the Biblical story from Genesis about the great flood. This aquatic theme would hold for the movie that lit the touchpaper for the genre as we know it in 1933 – Deluge.

RKO optioned the 1928 novel of the same name by S. Fowler Wright, with the setting changed from the United Kingdom to the United States. It follows a small group of survivors after a series of unexplained natural disasters erupt around the world and destroy human civilization, including a massive tsunami that strikes New York City.

This was a coming of age for the kind of miniature work on which the genre would come to rely, with scenes of waves swamping New York. There was also a heavy dose of human melodrama. The movie may have only been a modest success, but others followed such as The Last Days of Pompeii (1935) and John Ford’s The Hurricane (1937). King Kong (1933) also featured widespread city destruction at the hands of a rampaging force of nature. The movies, and the spectacle contained within them, were growing exponentially.

The Hurricane showed a tropical cyclone ripping through a fictional South Pacific island, while San Francisco (1936) recreated the historic 1906 San Francisco earthquake and In Old Chicago (1937) recreated The Great Chicago Fire which burned through the city in 1871. Across the pond in the UK, things were typically understated in Carol Reed’s 1939 film, The Stars Look Down, telling the story of a disaster at a coal mine in North-East England.

Just as it seemed that they were running out of natural disasters, the coming of the atomic age and the era of great scientific progress would mean that the well would never run dry for things to potentially cause humanity’s doom on the big screen. We began to look to the stars for our nemesis with When Worlds Collide (1951) and The War of the Worlds (1953). Meanwhile, in Japan, the lingering fear of atomic destruction gave birth to Godzilla.

Hollywood wanted some more of this giant monster action and so The Deadly Mantis was born. The monster movie was produced by William Alland for Universal-International. The film was directed by Nathan Juran from a screenplay by Martin Berkeley based on a story by producer William Alland. Craig Stevens, William Hopper, Alix Talton, and Pat Conway starred in the first science fiction creature feature made by director Nathan Juran, who has always claimed that the opening sequence was his creation.

In the South Seas, a volcano explodes, eventually causing North Pole icebergs to shift. Below the melting polar ice caps, a 200-foot-long praying mantis, trapped in the ice for millions of years, begins to stir.

To create special effects for The Deadly Mantis, a 200-foot (61 m) by 40-foot (12 m) long papier-maché model of a mantis, with a wingspan of 150 feet (46 m) and fitted with a hydraulic system, was built. A staggering achievement at the time. Two smaller models were also built, one that was 6 feet (1.8 m) long, and another that was 1 foot (0.30 m) long. These were to be used for the scenes where the mantis walked or flew. Shots of a real praying mantis were used for the famous scene in which the deadly mantis climbs the Washington Monument.

The Deadly Mantis also kickstarted the trend of heavily utilizing stock footage from the armed forces. They used Air Force-provided footage from their short films Guardians All, One Plane – One Bomb, and SFP308. The moviemakers even raided the Universal vault for footage of an Inuit village, using shots from the 1933 movie S.O.S. Iceberg.

Look Out! Volcano!

Volcanos would continue to cause a rich vein of disaster to be mined through The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961), Crack in the World (1965), and The Devil at 4 O’Clock (1961) starring Spencer Tracy and Frank Sinatra.

These led to another anchor point in the history of the disaster movie, the 1969 epic Krakatoa, East of Java starring Maximilian Schell.

As far back as February 1955, Philip Yordan announced he would write and produce a film of the Krakatoa eruption with a budget of US$2 million to US$3 million being spent on special effects. It was due to be the first movie made under Yordan’s contract with Columbia Pictures. Then nothing happened. The movie languished in development hell for more than a decade.

In January 1967 he started to film background footage for the movie in Indonesia and wanted Rock Hudson to star. Bernard L. Kowalski was attached to direct, having impressed on TV with shows like Mission Impossible and The Rat Patrol. Kowalksi himself said:

“That seemed to impress the Cinerama people who were looking for a young director who could handle what looked to be a pretty difficult picture.”

The script was being secretly co-written by Bernard Gordon, who had been blacklisted in Hollywood. This didn’t stop the production. The producers of Krakatoa, East of Java had the special effects scenes shot before the script had been completed. The script then was written to incorporate the special effects sequences. This approach feels familiar today in certain Hollywood movies.

Alongside natural disasters, man’s technological advancement would continue to allow filmmakers to create on-screen peril. Bigger ships, higher-flying aircraft, errant experiments. All would serve as the backdrop to bigger, more spectacular opportunities to wow audiences.

The Titanic kept floating around as a subject for disaster movies. Werner Klingler and Herbert Selpin released the epic film Titanic in 1943. The movie was soon banned in Germany and its director, Selpin, was allegedly executed.

The film was such a well-regarded adaption that the footage found its way into the Clifton Webb and Barbara Stanwyck 1953 movie Titanic from 20th Century Fox production, and the seminal British classic A Night to Remember in 1958.

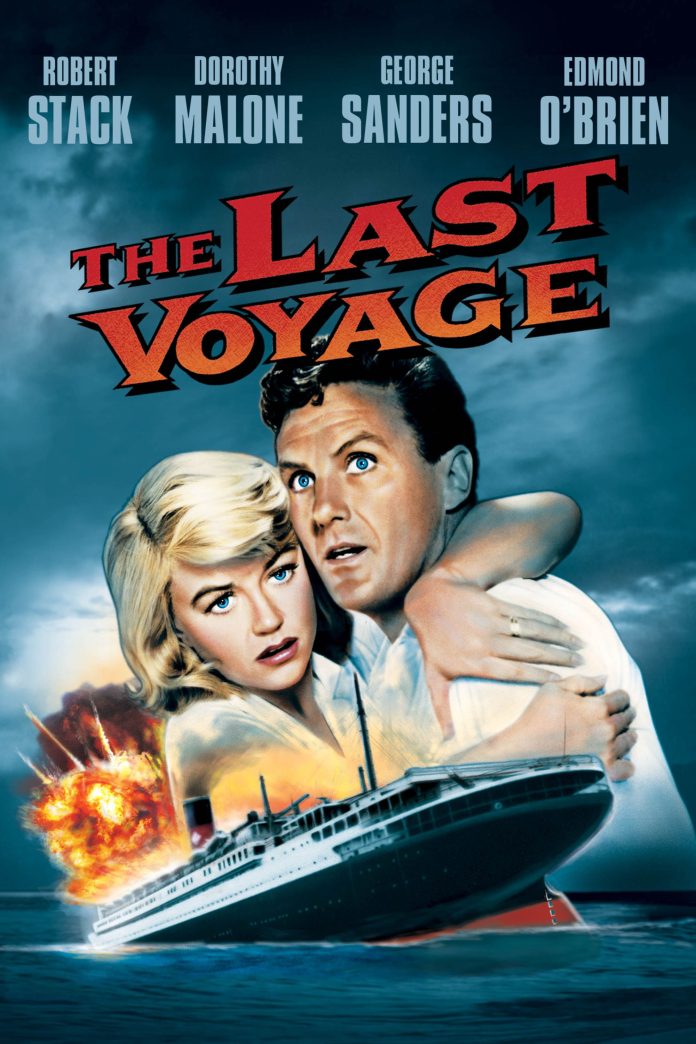

This fascination with the famous liner, and the watery setting for disaster movies, paved the way for another movie. The Last Voyage (1960) starred Robert Stack as a man desperately attempting to save his wife (Dorothy Malone) and child trapped in a sinking ocean liner. The dramatic sinking of the ship was nominated for an Oscar for Best Visual Effects. This movie would serve as a major inspiration for a movie that would soon form part of the golden-age for the genre.

Meanwhile, up in the air, the same was happening.

The High and the Mighty (1954) starred John Wayne and Robert Stack as pilots of a crippled airplane attempting to cross the ocean. Zero Hour! (1957) was written by Arthur Hailey (who would go on to write the novel Airport) and was about an airplane crew that succumbs to food poisoning. You will recognize this storyline from a certain famous parody that was actually based on this story as a starting point for the silliness to follow.

Jet Storm and Jet Over the Atlantic were both made in 1959 and both featured attempts to blow up an airplane in mid-flight. The Crowded Sky (1960) depicted a mid-air collision.

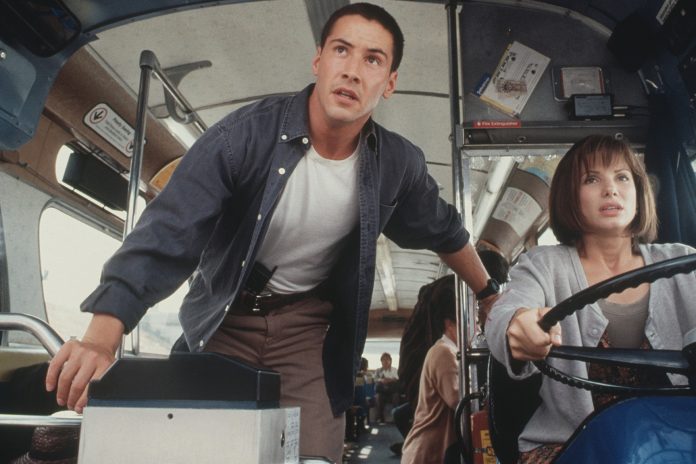

The Doomsday Flight (1966), written by Rod Serling, starred Edmond O’Brien as a disgruntled aerospace engineer who plants a barometric pressure bomb on an airliner built by his former employer set to explode when the airliner descends past a certain point. Say… almost like a bus that can’t slow down? Woah!

Speed screenwriter Graham Yost would always deny that this movie served as his inspiration, but those of us that know, know.

Sinking ships, crippled airplanes, rampaging weather… the scene was set for what would become the golden age of disaster movies.

The Master Of Disaster

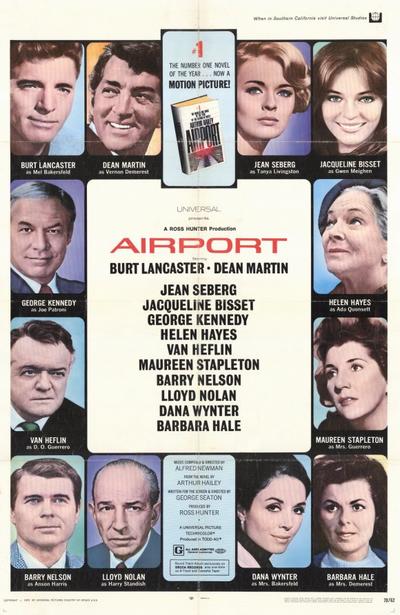

Arthur Hailey had already written Zero Hour! When his follow-up novel Airport was adapted in 1970, the disaster movie truly arrived. It was a huge financial success earning more than $100 million ($620 million in adjusted dollars), at the box office. It surpassed Spartacus as Universal’s biggest earner at this point.

Directed by George Seaton, it starred Burt Lancaster, Dean Martin, George Kennedy, Jacqueline Bisset, and Helen Hayes. The ensemble cast, the nefarious scheme causing the disaster, the human foibles of the heroes… the blueprint was all there and executed perfectly.

The movie is still praised today for the attention paid to the detail of day-to-day airport and airline operations while wrestling with the response to a paralyzing snowstorm, environmental concerns over noise pollution, and an attempt to blow up an airliner.

The personal stories intertwine while decisions are made minute-by-minute by the airport and airline staff, operations and maintenance crews, flight crews, and Federal Aviation Administration air traffic controllers. Even today it’s a masterclass of how to execute in the genre.

Seeing this, a young television producer with a big idea seized his chance.

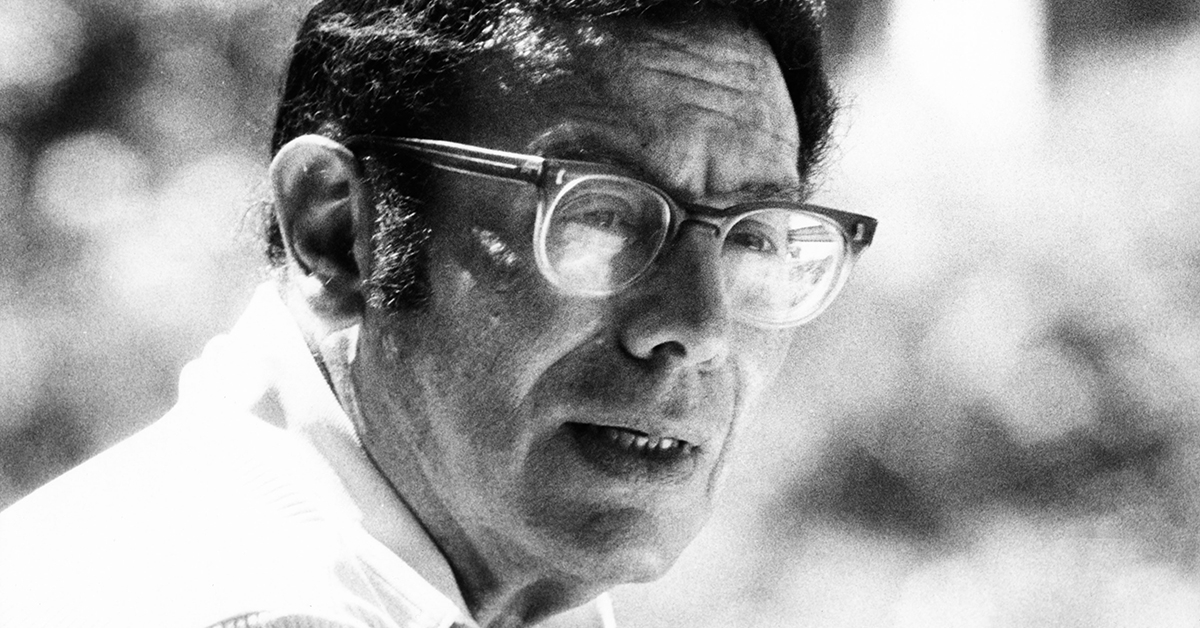

Irwin Allen was born in New York City, the son of poor Jewish immigrants from Russia. He majored in journalism and advertising at Columbia University after attending City College of New York for a year. He left college because of financial difficulties caused by the Great Depression.

Allen moved to Hollywood in 1938, where he edited Key magazine followed by an 11-year stint producing his own program at radio station KLAC. The success of the radio show led to him being offered his own gossip column, Hollywood Merry-Go-Round, which was syndicated to 73 newspapers.

He produced his first TV program, a celebrity panel show also called Hollywood Merry-Go-Round with announcer, and later Tonight Show host, Steve Allen who was not his relation.

He made his name across RKO and Warner Bros focussing on TV, and was then working at Universal. He was known for his work in science fiction on the small screen. Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space, The Time Tunnel, and Land of the Giants were all from his producing stable.

He was fascinated by circuses as a child and briefly worked as a carnival barker at age 16. In addition to his feature film The Big Circus, he worked circus-themed episodes into his TV programs Lost in Space and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea. He also instigated a widescreen 3-D project called Circus, Circus, Circus. He saw the disaster genre as his opportunity to deliver something that had the showmanship of P. T. Barnum with the scale of Cecil B. DeMille, so he signed a deal with Avco Pictures, and The Poseidon Adventure was born.

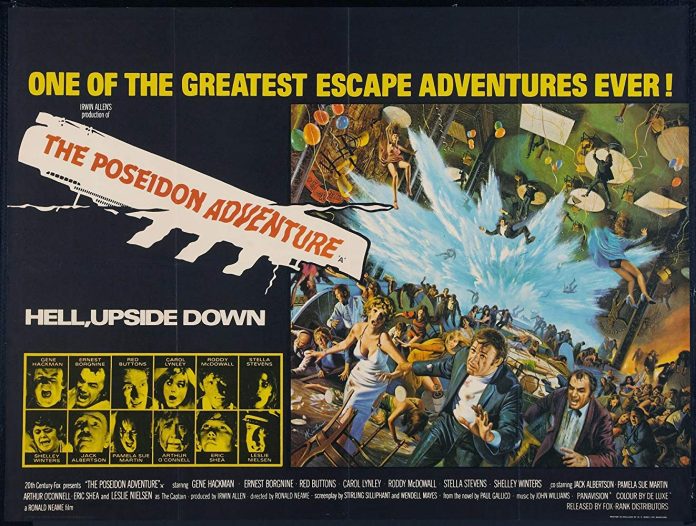

The 1972 release of The Poseidon Adventure was a huge financial success. $84 million in the US & Canada alone makes more than $500 million today. It heralded the disaster genre as an official movie-going “craze” or trend. Directed by Ronald Neame and starring Gene Hackman, Ernest Borgnine, Shelley Winters, and Red Buttons, it was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Supporting Actress for Shelley Winters. It won the award for Original Song and a Special Achievement Award for visual effects.

The Golden Age Of Disaster Movies

Following Airport and The Poseidon Adventure, all studios wanted bigger, badder disasters. Several movies were fast-tracked. Money was no object and the greatest stars were wooed to join the productions. They grew so big that when Irwin Allen dreamt up the greatest disaster movie of them all, it forced collaboration between two movie studios.

The Towering Inferno is a tale of “Two”. It was a co-production between 20th Century-Fox and Warner Bros., and thus the first film to be a joint venture by two major Hollywood studios. It was adapted by Stirling Silliphant from two novels The Tower (1973) by Richard Martin Stern and The Glass Inferno (1974) by Thomas N. Scortia and Frank M. Robinson.

It starred two of the biggest stars of the day in Steve McQueen and Paul Newman. It even faced a dilemma about how to give them both top billing, leading to the famous offset appearance of their names in the credits and on posters.

The Towering Inferno was the highest-grossing movie of 1974 and was nominated for eight Oscars including Best Picture. Back then, the genre was serious business. Possibly the greatest cast ever assembled includes William Holden, Faye Dunaway, Fred Astaire, Susan Blakely, Richard Chamberlain, O. J. Simpson, Robert Vaughn, Robert Wagner, Susan Flannery, Gregory Sierra, Dabney Coleman and, in her final role, Jennifer Jones

The golden age was off and running. Earthquake and Airport 1975 (the first Airport sequel) followed. The returns were enormous. The Towering Inferno earned $116 million, which is over $660 million in adjusted dollars, Earthquake earned $79 million (over $450 million adjusted), and Airport 1975 earned $47 million (over $270 million adjusted).

Earthquake was also honored with four Academy Award nominations for its impressive special effects of a massive earthquake leveling the city of Los Angeles, winning for Best Sound, and receiving a Special Achievement Award for visual effects.

TV was not to be left out. Made-for-TV disaster movies proliferated and Heatwave! (1974) was followed by The Day the Earth Moved (1974), Hurricane (1974), Flood! (1976) and Fire! (1977). You couldn’t turn around without seeing some disaster, death, and destruction as entertainment somewhere.

The Hindenburg (1975) starring George C. Scott, The Cassandra Crossing (1976) starring Burt Lancaster, Two-Minute Warning (1976) starring Charlton Heston, Rollercoaster (1977) starring George Segal, Avalanche (1978) starring Rock Hudson, and City on Fire (1979) starring Barry Newman. The movies just kept on coming.

Then things started to go wrong. Saturation point was reached. Even the biggest stars, and Irwin Allen’s name over the door, could not halt the slide.

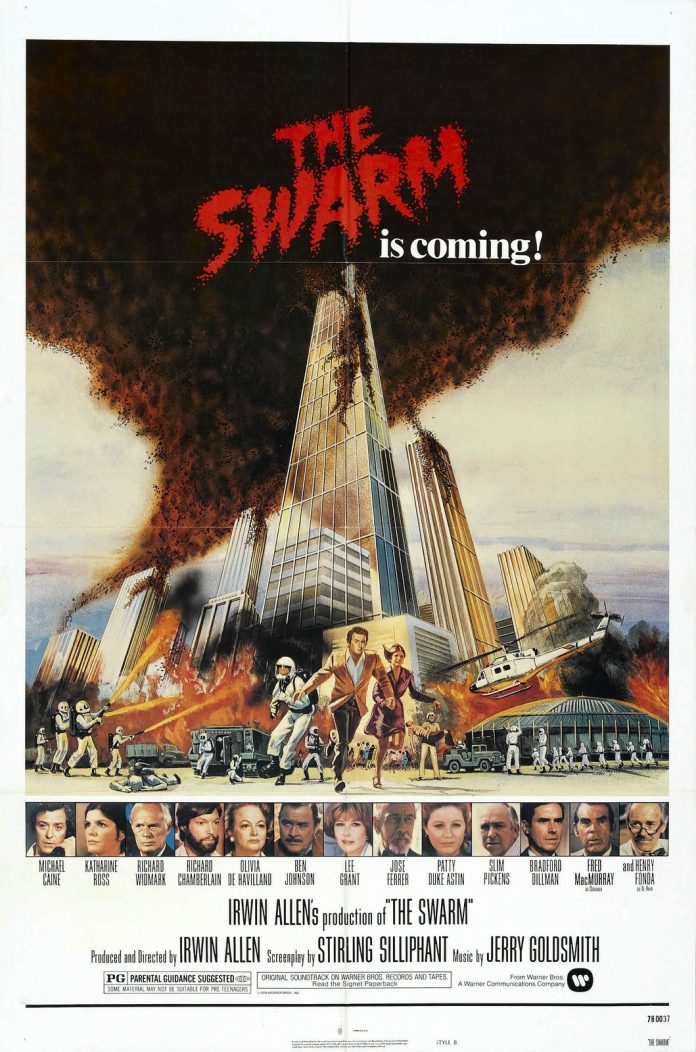

The Swarm, Meteor, Hurricane, The Concorde: Airport ’79, Beyond the Poseidon Adventure (1979), and When Time Ran Out (1980) all performed increasingly poorly at the box office. Even star powers like Michael Caine and Sean Connery couldn’t push people to theaters for more of the same. The decline had arrived.

The final harbinger of the decline? The parody. When a genre has reached the top and started the fall, the parody will follow. It is a rule of cinema.

The genre was bracketed by two notable spoofs. The Big Bus (1976) and Airplane (1980). Airplane was a comedy adaption of the earlier Zero Hour! and was such a success it spawned its own sequel.

CGI Strikes Back

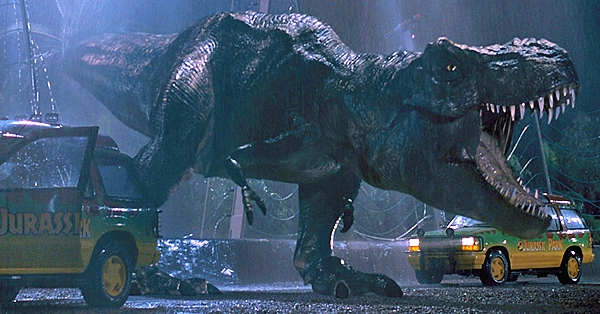

The ballooning budgets and serious decline in public interest caused by oversaturation meant that the disaster movie all but disappeared for over a decade. Then, in 1993, something happened.

The effects in Jurassic Park not only convinced George Lucas that the technology had finally caught up with his vision and he should return to Star Wars. It showed a whole new generation of filmmakers that anything was possible.

Audiences want big spectacle, but without the limitations of 1970s VFX. Suddenly, the disaster movie was back in a big way!

Twister, Independence Day, Daylight, Dante’s Peak, Volcano, Hard Rain, Deep Impact, and Armageddon. The movies came back with new computer wizardry at their heart.

The one subject that had inspired early disaster movies, and that had cropped up again and again, also made a return. In 1997, James Cameron produced, wrote, and directed Titanic. The movie combined romance, human drama, death, and destruction with intricate special effects in the finest traditions of the big-budget disaster movies of the 1970s.

It smashed all records and exceeded expectations. It went on to become the highest-grossing movie of all time and remained in that number-one spot for 12 years. With $2.1 billion worldwide in takings and 11 Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director, it was like the golden age was back again.

In this age, an heir apparent to Irwin Allen emerged. Harnessing visual effects ambition with a love of large-scale destruction, Roland Emmerich became known for his huge, landmark, and city-destroying set pieces. After Independence Day came Godzilla (1998), The Day After Tomorrow (2004), and 2012 (2009). They all made good money.

However, just like the 1970s, the genre was over-saturating again. This brings us to the most recent – Moonfall. A box office disaster.

It’s true. Cinema really does just move in cycles.

Check back every day for movie news and reviews at the Last Movie Outpost