Rage (1972) stars George C. Scott, the man who looks like a potato but can act like a boid.

I came across Rage after referring to George C. Scott in a post Boba made about the latest entry in a franchise that shall not be named. A few facts caught my eye:

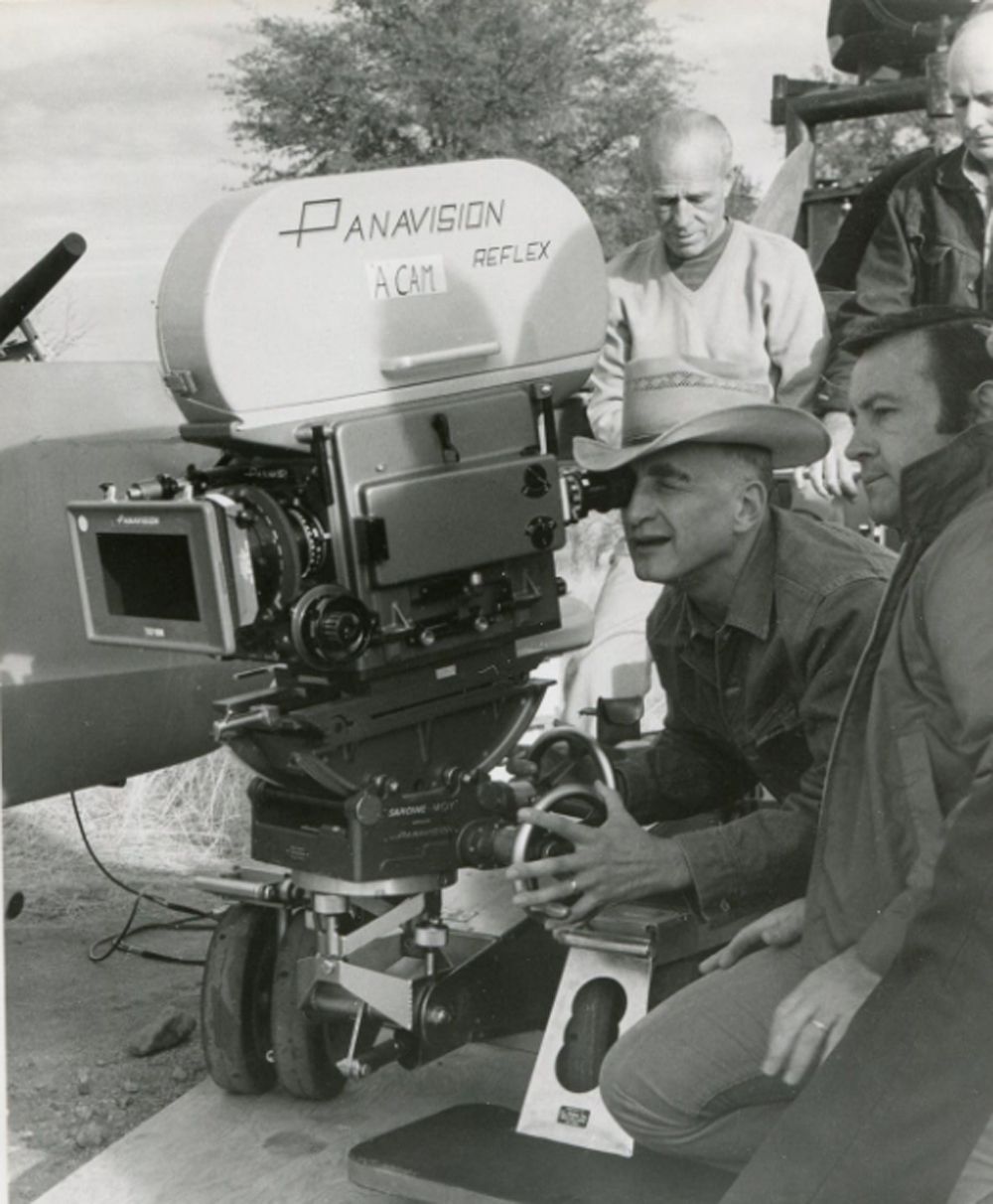

Scott sat in the director chair for Rage; it’s a leaked-chemical-weapon movie like The Crazies, Endangered Species and Impulse; and Rage is one of Quentin Tarantino’s favorite movies.

Add all that up, and Rage must be watched. Spoilers will happen because it is not quite worth the hype, yet it is interesting in its own unique way.

Rage

Reviews were not particularly kind to Rage upon its release. Scott’s direction was singled out by Gene Siskel as part of the problem.

“As good an actor as he is, and ‘Rage’ is a decent example of his strength, Scott is a dismal director. The film includes would-be arty slow-motion shots of coffee being thrown on a campfire, sedatives being handed to a hospital patient, and a cat jumping on a sofa. None of them make any sense except as errors by a fledgling director.”

Truth exists to this statement. Scott does do head-scratching things. The oddest one is where he films a disgusting slow-motion shot of him spitting tobacco. The shot is part of an odd technique he uses a lot in the opening of the film and a couple of other times later on.

Scott seemingly took inspiration from 2001 for this. At the end of 2001, Kubrick messes with the passage of time by panning from Keir Dullea at one age to Keir Dullea at another age. It works great.

In Rage, Scott pans from him doing farm activities with his son to doing more farm activities with his son, all without notable cuts to denote time passing between the activities.

It is a bit jarring but works. Scott is trying to show that the life he and his son had was one where each day blurred into the next without any change in their affection for one another.

Streets of Rage

Joining Scott is a good supporting cast of Richard Basehart (Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea), Martin Sheen and good old Ed Lauter. A couple other familiar faces also show up.

It took me a while to recognize Barnard Hughes before realizing he was Grandpa from The Lost Boys. Kenneth Tobey (The Thing From Another World) makes an appearance, as well, as an Army general.

Rage works the best in its first half. Scott and his son are exposed to a chemical weapon while out camping. Since Scott is in a tent, he takes less of a dose than his boy, who slept outside by the fire. Scott quickly takes his unconscious, pants-wetting son to the hospital.

Once at the hospital, Rage becomes a conspiracy-thriller as Scott and his son are separated by Sheen, who plays a doctor in cahoots with the Army.

Sheen keeps Scott drugged and lies to him about the condition of his son, who dies shortly after being admitted. Meanwhile, Hughes is an Army liaison officer working to keep what happened a secret from the public.

The shot of a nurse dispensing sedatives in slow motion happens at this point. It causes no great distraction, however, as Scott has already established slow motion as one of his techniques. It is certainly not as distracting as Peckinpah’s use of slow motion in The Killer Elite.

The first half of Rage culminates with Scott sneaking out of his room, entering the morgue and discovering the death of his son. Scott displayed a deft touch here, as well.

This could have been a drawn-out scene of Scott weeping over his boy’s body. Instead, a simple shot of Scott seeing his boy’s name on a corpse drawer is more than enough to convey the emotions he’s dealing with.

Rage of Honor

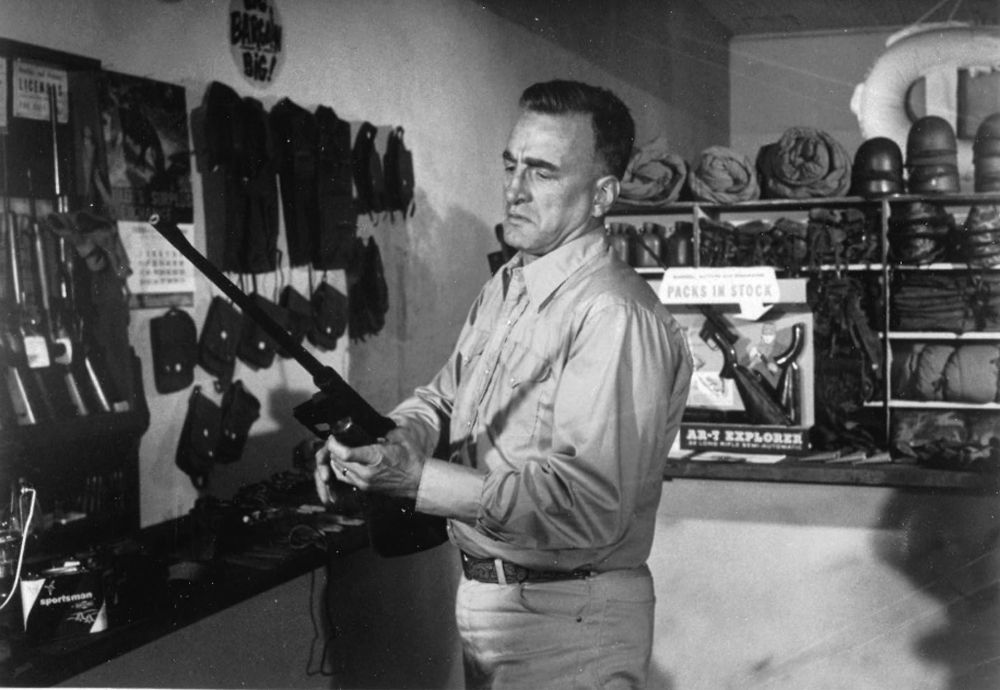

The second half of Rage kicks in, and things go a bit…awry. Elements are there for a rip-roaring conclusion: Scott is slowly dying from his exposure to the chemical, and he procures a motorcycle, a gun and a box of dynamite. This is prime 70s-revenge-flick stuff.

Unfortunately (or fortunately, if you are of Quentin Taratino’s taste), Scott doesn’t give the viewer exactly what they want to see. In fact, I’m not exactly sure what I saw.

First, Scott visits Hughes at home. The slow-motion cat sequence happens here. Such a thing can be explained thematically…maybe. Scott is perhaps a cat playing with its food as he confronts Hughes. Yet, the scene culminates in one of the most what-the-heck moments I have witnessed.

The cat jumps on a chair. Scott spins with a snarl and absolutely annihilates the feline with about five shots from his twenty-two-caliber survival rifle. All that’s left of the cat is blood-splatter.

Admittedly, this moment alone makes me want to give Rage five stars, but that would be wrong…

Scott is not finished with his wrath upon animals either. A lengthy sequence follows where Scott blows up a laboratory. At one point, finds himself in a room with a bunch of animals in cages: puppies, rabbits, the whole bit.

Scott looks around at all of these cuddly creatures, seemingly comes to the conclusion of screw it, lights a bundle of dynamite, tosses it on the floor and leaves. Take that, fluffy!

Rage Against the Dying of the Light

Rage ends with Scott hijacking a truck and driving to the military base with a box of dynamite. The viewer gets the vibe that they will see the ending from The Running Man novel happen.

Instead, Scott’s character dies in the spotlight of a helicopter while having a seizure. The next morning, Scott’s corpse is loaded up and no doubt taken somewhere to be dissected.

Rage ends with the shot of a softball game breaking out where Scott died.

Okay…that does not follow the usual formula. Yet, it is 1970s storytelling. Filmmakers in the 1970s weren’t afraid to go hard with cynical endings.

Did all of this happen at the screenplay level? Philip Friedman was one of the writers on Rage. It’s his only credit. The other writer is Dan Kleinman, who is also short on credits. He wrote Rage, an episode of Tales From The Dark Side, a post-apocalyptic barbarian movie called Ultra Warrior and then disappeared until 2018 with Tel Aviv on Fire.

None of that reveals much. Since Scott displays evidence of trying to do something artistic with earlier parts of Rage, one tries to follow that line through the whole thing. Scott’s character dying in the spotlight of a helicopter could be an allusion to the phrase “going into the light” when it comes to death.

Likewise, when Scott is hauled away by the helicopter at the end, his corpse has a slight smile on its face as the earth dwindles beneath him. This could be a reference to heavenly ascension.

The impromptu softball game on his death site is Scott, perhaps, saying that despite all of the bad things that happen to good people, life goes on and people play among their bones.

Despite of my Rage, I am Still Just a Rat in a Cage

Elements of Rage are enjoyable. Scott is fun to watch. It was surprising to see him this spry in a movie. Usually, he comes across as pretty sedentary. In Rage, he farms, rides motorcycles, runs and blows things up. His performance is fine across the board, going from loving, to concerned, to confused, to angry, to deadly and slightly unhinged as the chemical wears him down.

Scott also displays a fine eye from the director’s chair. Rage has some nice sweeping aerial shots of, what I guess is, Wyoming, and Scott’s framing of certain scenes is pleasing to view. I especially liked the shot of him watching an approaching helicopter.

Scott is clearly trying. Another example is a shot of him driving a motorcycle. It could be a simple shot with a camera driving beside him. Instead, the camera comes up behind Scott while parked. Scott starts driving, the camera passes in front of him, goes to the other side and pulls ahead. All of this is done without raising any dust on a dirt road, so it would have taken some prep.

One’s enjoyment of Rage comes down to whether or not they enjoy Scott’s attempt to seemingly do a bit more with what should be a straight-forward conspiracy/revenge flick. They will either appreciate the little nuances he brings to the director’s chair or they won’t.

Personally, I was able to watch Rage all the way through in one setting, which is a rare and wonderful thing for me these days. I would have liked to see Scott make different choices, but watching what a great actor, who made his living in front of the camera, brings to the backside of the lens was interesting enough to keep my attention.

Plus, there is something to appreciate about movies that weren’t written by Excel. When stories aren’t written by Excel, weird things can happen, and movies like Rage end up as the result.