It’s hard to go wrong with the one-two-punch of Alfred Hitchcock and Jimmy Stewart. Yet, it does go wrong in Rope (1948).

Play Out The Rope

Rope was Hitchcock’s first Technicolor film. It is based on a play written by Patrick Hamilton. Hume Cronyn adapted the play to the screen. Outposters will recognize Cronyn from such films as The Parallax View and Cocoon.

The original play was inspired by the real-life murder of a 14-year-old boy, Bobby Franks. Franks was killed by a pair of University of Chicago students, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb. The murder was not committed for money or passion. Rather, Leopold and Loeb got it in their heads to see if they could get away with the perfect crime. They then carried out their plan on Franks.

Throw Me A Rope

Rope is something of an experimental film. It takes place in a single location in real-time. Its 80-minute runtime is done in takes up to 10 minutes long (the length of a film camera magazine). Most of the cuts are hidden by the camera moving into a character’s back and panning off of it. This is similar to what Spielberg did in Jaws during the death of Alex Kintner, where cuts come off passing beachgoers.

All of this required meticulous planning. Performers had to know their lines and cues as the camera danced among them. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, crewmembers moved furniture out of the way and back again. They could even pull out entire sections of wall to enable the camera to get to where it needed to be and then replace the wall when the camera returned.

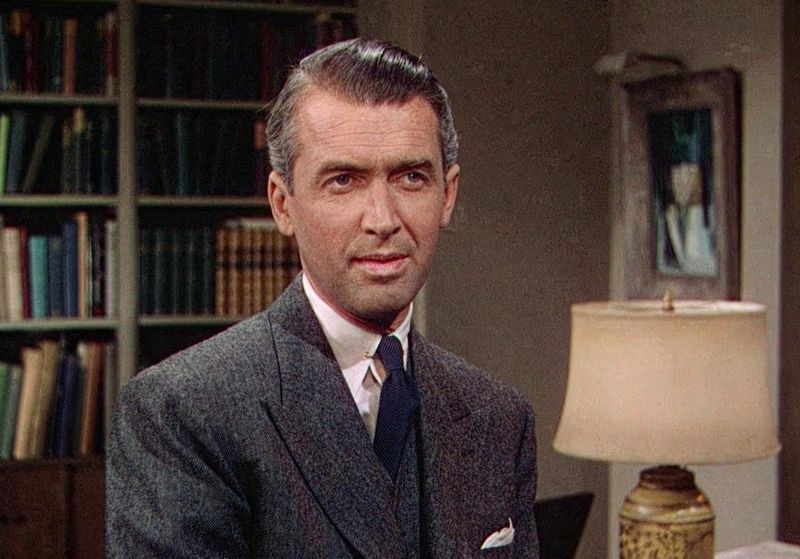

“The really important thing being rehearsed here is the camera, not the actors,” Stewart said of the process. “It was worth trying – nobody but Hitch would have tried it. But it really didn’t work.”

Another part of the illusion was the cyclorama outside the apartment windows. It was the largest backing used on a sound stage. It included models of the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings, plus smoking chimneys, lights, neon signs, and a setting sun. Clouds were made of spun glass and changed shapes and positions. Still not as cool as the cyclorama in Die Hard, though…

DIE HARD (1988) 🎄🎅

This is the actual cyclorama used for the distant city background, seen from the top of the Nakatomi Plaza. 🏬#VFX #VFXHistory pic.twitter.com/zAYcekt3rh— Ludo Iochem (@ludoviciochem) November 28, 2023

Roping The Cast

The murderous duo is played by John Dall (Spartacus) and Farley Granger (Strangers on a Train). Dall is the alpha member. He moves through the film with a smarmy arrogance, enjoying the thrill of hosting a dinner party where food is served off a chest that contains a dead man.

Granger is Dall’s histrionic partner. One gets the sense that his character gives into peer pressure easily.

Dick Hogan portrays the murder victim. Hogan is killed within the first minute of the film and is not seen again. Interestingly enough, Rope was Hogan’s last movie. He was not seen in Hollywood again after it. He moved to Little Rock, Arkansas and became an insurance salesman.

The rest of the cast is filled out with Joan Chandler and Douglas Dick as an estranged couple. Cedric Hardwicke (who provided the commentary voice on the 1953 War of the Worlds) is the victim’s father. Contance Collier portrays a flamboyant Angela Lansbury-type. Edith Evanson (The Day The Earth Stood Still) star as the housekeeper.

Jimmy Stewart plays a publisher whose cynical philosophy on human life motivates Dall and Granger to embark on their murderous shenanigans. As usual, Stewart is the highlight of the film. He navigates Rope like a lazy shark, drolly dishing out subtle insults while puzzling out what happened.

As strong as Stewart is, his character is the main reason the movie falters in the end. Dall and Granger’s motivations are based on things Stewart’s character said to them in their school days. Hence, the viewer wonders if Stewart is going to go along with them or turn the tables on the killers by revealing himself to be an even more clever killer.

Instead, Stewart gives a speech on the sanctity of life and how wrong the psychotic duo is in thinking superior intelligence gives them the right to murder. Certainly, it’s a noble thought and one to aspire to in real life. Yet, in movieland, it doesn’t quite gel into a satisfying viewing experience.

Dropped Soap-On-A-Rope

Rope is notable for a homosexual subtext between Dall and Granger. This is not surprising since Dall and Granger were both gay. Yet, this is Old Hollywood Homosexuality, not New Hollywood Homosexuality. Those involved are operating from the closet, which is better in retrospect. In a post-coming-out world, homosexuality shows it is not content to have a seat at the party. It wants a pulpit.

For this reason, murderous homosexuals would not make it into a movie today. It’s too negative for the messaging. Only the Magical Negro version of homosexuality is allowed.

As for Rope, no real reason for a homosexual angle needs to exist in the story. It is maybe there for Hitchcock’s amusement. He didn’t have an icy blond to creep on in Rope, so he had to find other ways to get his chuckles. Here, the snickers come out in a scene where Granger refuses to admit to wringing the necks of chickens.

Modern translation: he’s not a chicken choker, folks – in the most lady-doth-protest-too-much way possible.

This juvenile approach to a risqué subject, combined with some experimental filming techniques are really all Rope has to hang onto to justify any special status. Probably its best scene is when the housekeeper starts clearing off the trunk that contains the dead body in an unbroken sequence of going back and forth from the kitchen to the chest.

The End Of Your Rope

Rope is not among Hitchcock’s best work. Yet, even when he isn’t at his best, it’s hard for him to not at least be somewhat interesting. Rope is interesting to watch, but it never truly hooks the viewer due to not having a real plot. It is simply a bunch of people sitting around an apartment, spouting overly-clever lines while a dead body sits in a trunk.

Hitchcock famously said that the difference between surprise and suspense is this: when a bomb goes off unexpectedly, that is surprise; when the viewer is shown the bomb, and the characters don’t know about it, that is suspense.

Hitchcock shows us the bomb in Rope in the form of the dead body, but he never gives us the explosion. All he gives us is the sound of police sirens wailing in the distance. We don’t even get left with any questions to ponder. Everything is answered for us. Essentially, Rope uses up all of the slack it is given.